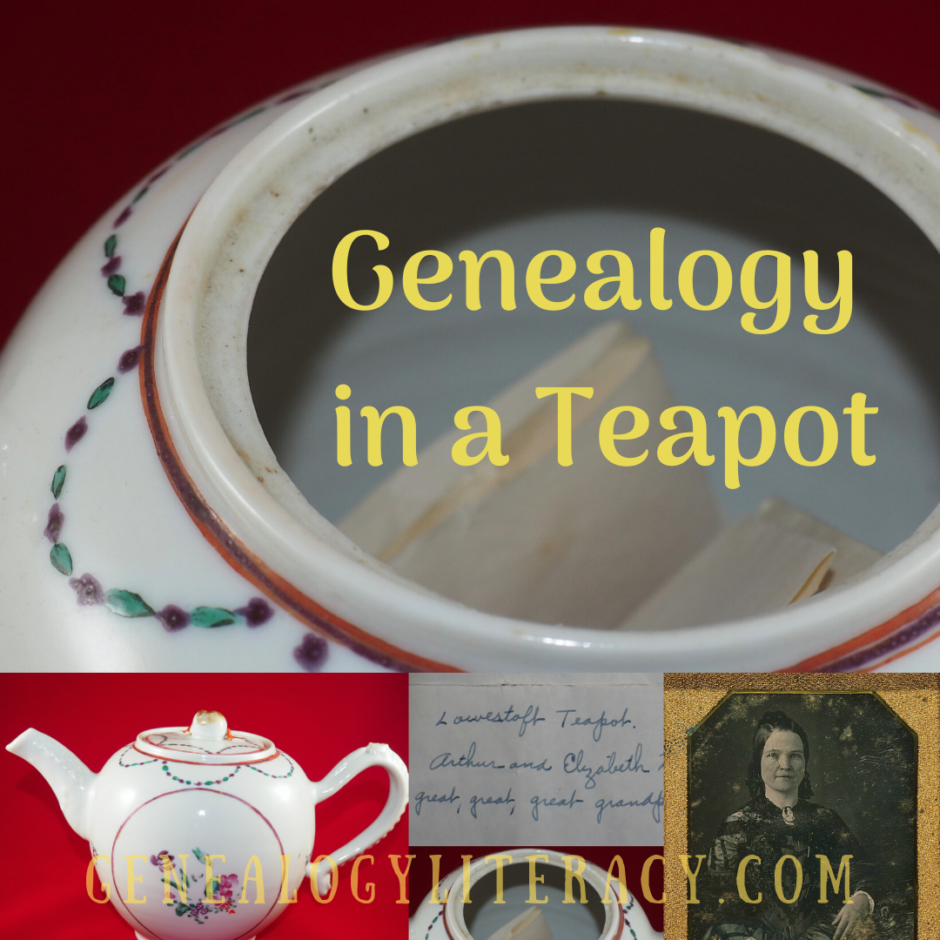

One of my most recent teapot purchases came with an amazing surprise.

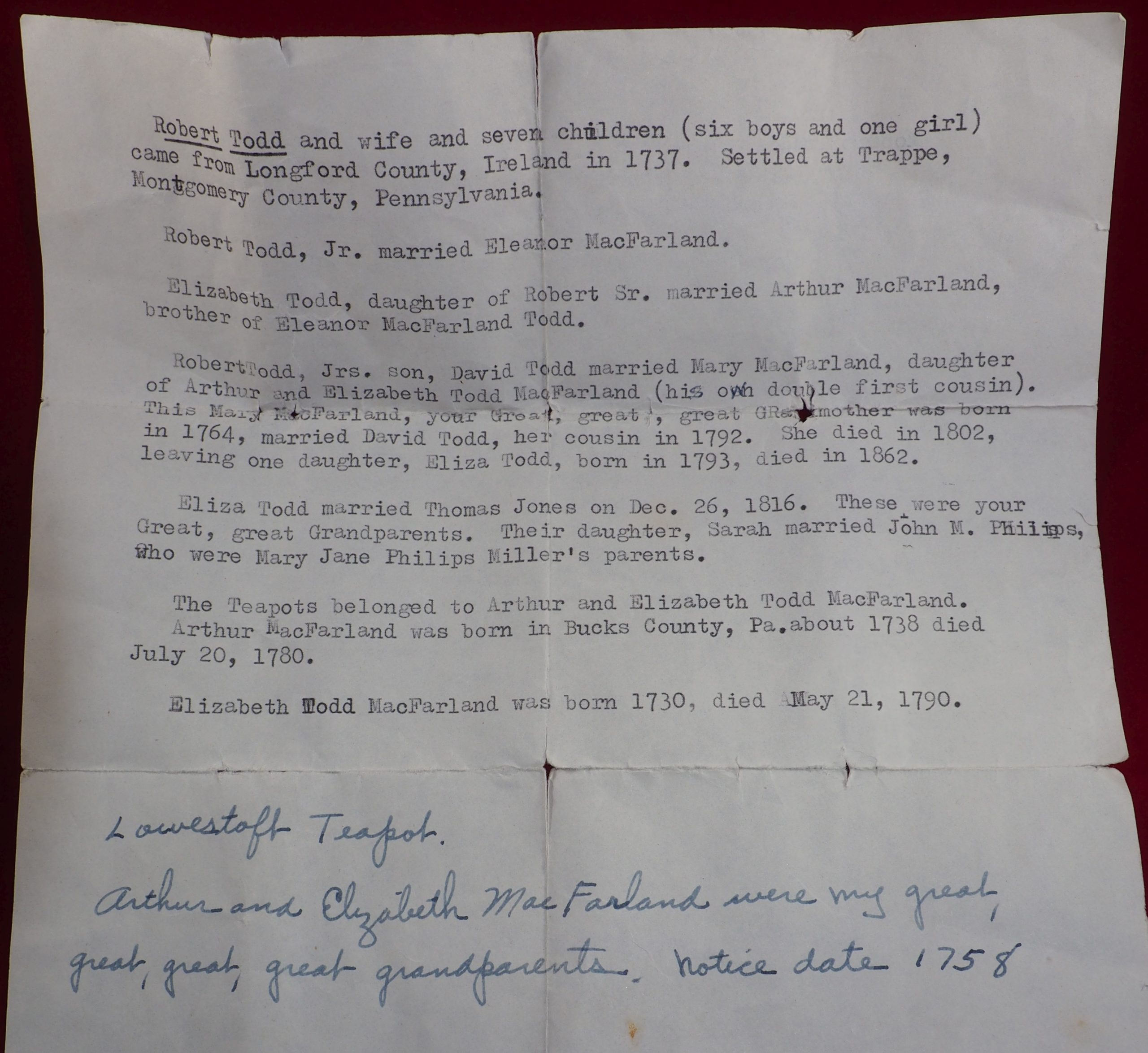

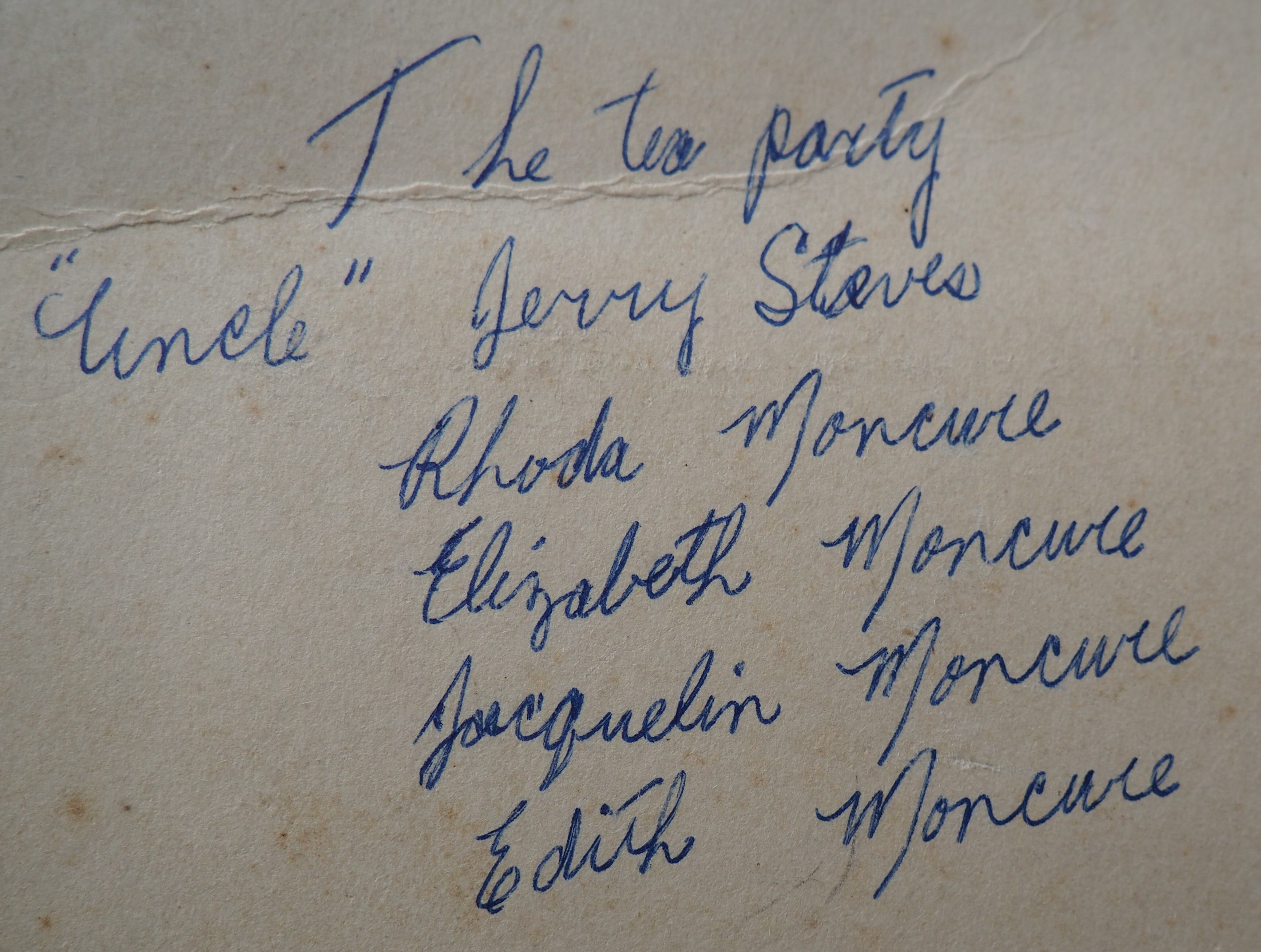

A note was folded up and placed inside this 18th century porcelain beauty….a note that detailed its genealogy of ownership. Sadly, the ownership chain had been broken for a few decades as the last generational owner passed away. But the delight in finding anything about the original owner of such a teapot was beyond my wildest dreams.

As you can see from the note, it has a long history, of immigration, lineage, weddings, and familial intermarriage to the cousin level. And in one case, the “double cousin” level. It also mentions TWO teapots, but this is the only one discovered.

After reading all of the begats, I looked at the front of the teapot, and sure enough, there was a label that had been added at some point, to celebrate the marriage of Arthur and Elizabeth Todd McFarland in 1758.

Due to the wear of the writing, I’m not sure how close to the event this was added. Since it was a wedding gift, perhaps it was added in 1758? After seeing other examples of added glaze decoration, this just doesn’t feel right for a 1758 label. I could be wrong, and perhaps it was just a sloppy job? Either way, the half worn appliqué is a lovely addition tying the teapot to its place in history.

After completing my obligatory happy dance at such a discovery, I got serious about matters and inquired further with the seller concerning the provenance. After all, I was afraid this person was parting with a family heirloom. On the contrary, while it had belonged to his mother’s estate, she had purchased it years ago at a Church rummage sale next door to a nursing home in Florida. A bit of a relief, but still sad, nonetheless.

After completing my obligatory happy dance at such a discovery, I got serious about matters and inquired further with the seller concerning the provenance. After all, I was afraid this person was parting with a family heirloom. On the contrary, while it had belonged to his mother’s estate, she had purchased it years ago at a Church rummage sale next door to a nursing home in Florida. A bit of a relief, but still sad, nonetheless.

Once this little gem had made it home to my collection, I began going over the family connections. As a historian, the surname “Todd” was setting my wheels to turning. It couldn’t be, surely…not the same family as the other Todd clan we’ve all heard of.

So I started doing some research into this line. My first stop at Findagrave.com had me linking pretty quickly to the generation of Mary Todd Lincoln’s Great Grandfather….cue hyperventilating. Then I calmed down and started looking for corroboration.

According to a sweet little book entitled, Todd Family, Copied from Kittochtinny Magazine, 1905, also From the mss papers of Mrs. Emily Todd Helm by Nina M. Visscher, 1939, the lineage in the letter is spot on.

Some of the information was reported within a few generations of Elizabeth by Emilie (Emily) Todd Helm – Mary Todd Lincoln’s half sister – who became the Todd family historian. To spare you the gory genealogy details, this teapot belonged to Mary Todd Lincoln’s half-great great aunt, Elizabeth Todd Parker McFarland. Huzzah!

Remember the great grandfather I mentioned earlier? David Todd, son of Robert, “the immigrant”, was a child of Robert’s first marriage to “unknown” Smith. Poor girl, we’ve lost her given name over the years. Robert next married Isabella Hamilton and started having a lot more offspring. Elizabeth Todd (David’s half sister) was one of the next in line in order of birth. David’s descendant line stretches to Mary Todd Lincoln through his son Levi, to son Robert, and then to Mary Todd Lincoln. OK, you can uncross your eyes now…in linear fashion, this is what it looks like:

Robert Todd > David Todd (Elizabeth Todd McFarland’s half brother) > Levi Todd > Robert Todd > Mary Todd (Lincoln).

So, enough about Mary Todd Lincoln…here’s a bit more information about the happy couple who owned this teapot. It appears that Elizabeth was married previously to a William Parker. They had three children, and then he died around 1757. The very next year, Elizabeth marries Arthur McFarland in 1758. She wasn’t moving on too soon – this was common for widows to marry again as soon as possible – first, more men than women created quite the demand – second, women had little to no rights, and for protection/financial stability/survival, they needed a husband.

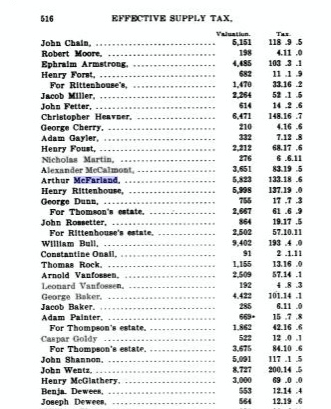

After Elizabeth and Arthur married in 1758, they have four more children. Arthur is listed in the Todd family history as “Major” Arthur McFarland. I have not been able to find record of this military service, but since he was born in 1720 and died in 1780, I’m guessing it’s not for service in the American Revolution. If it was for an earlier war, such as French and Indian, I’d have to keep digging. With a person of property during the Revolution, one naturally questions allegiance, and I’m happy to say that I found Arthur listed in the Philadelphia “Supply Tax” rolls for the year he died. This type of tax was taken from those who were supporting the cause of the Revolution.

After Elizabeth and Arthur married in 1758, they have four more children. Arthur is listed in the Todd family history as “Major” Arthur McFarland. I have not been able to find record of this military service, but since he was born in 1720 and died in 1780, I’m guessing it’s not for service in the American Revolution. If it was for an earlier war, such as French and Indian, I’d have to keep digging. With a person of property during the Revolution, one naturally questions allegiance, and I’m happy to say that I found Arthur listed in the Philadelphia “Supply Tax” rolls for the year he died. This type of tax was taken from those who were supporting the cause of the Revolution.

Elizabeth died May 21st, 1790, and she is buried alongside her second husband, Arthur McFarland in the Providence Presbyterian Church graveyard outside Philadelphia.

So, in light of these details, does this jibe with the details of the teapot itself? Does it look like a teapot made in 1758? One clue that was included in the family note referenced “Lowestoft.” This type of teapot was made in England at the time, but I feel this label is inaccurate. One of my favorite tools for learning how to visually understand porcelain terminology and teapot construction is the museum website.  Places like the MET and the Victoria and Albert Museum allow you to search their collections with terms you’ve come across. These are going to be wonderful experts in the matter, even over antiques dealers who might have good intentions, but lack sufficient expertise to get the variances correct. After all, no one is an expert in everything.

Places like the MET and the Victoria and Albert Museum allow you to search their collections with terms you’ve come across. These are going to be wonderful experts in the matter, even over antiques dealers who might have good intentions, but lack sufficient expertise to get the variances correct. After all, no one is an expert in everything.

At the end of the day, Lowestoft examples appear to have a slightly different shape, domed lid, and different decoration. This porcelain does fit into the small, rounded Chinese Export examples….but I’m no expert….just collecting and learning as I go. As for 1758, yeah, it fits OK there too. Other examples of this construction fit that time frame. Also, the imperfections, firing flaws, bottom look (sans mark), strainer area, handle attachment, and glaze embellishments fit with the period.

One other thing I love about this teapot is its very old repair. Somewhere along the timeline, the lid was broken in half. Due to its strong family connection, they had it repaired instead of tossing it altogether. This unsightly staple repair is typical of the 19th century, and produces another layer of charm to this storied teapot.

Moral of the story: Always look inside those teapots when heirloom hunting or antiquing. I adore teapots with stories or provenance tucked inside. This is not my only teapot with family information, but it is the only one I have that came complete with its own genealogy!

Happy hunting, y’all!

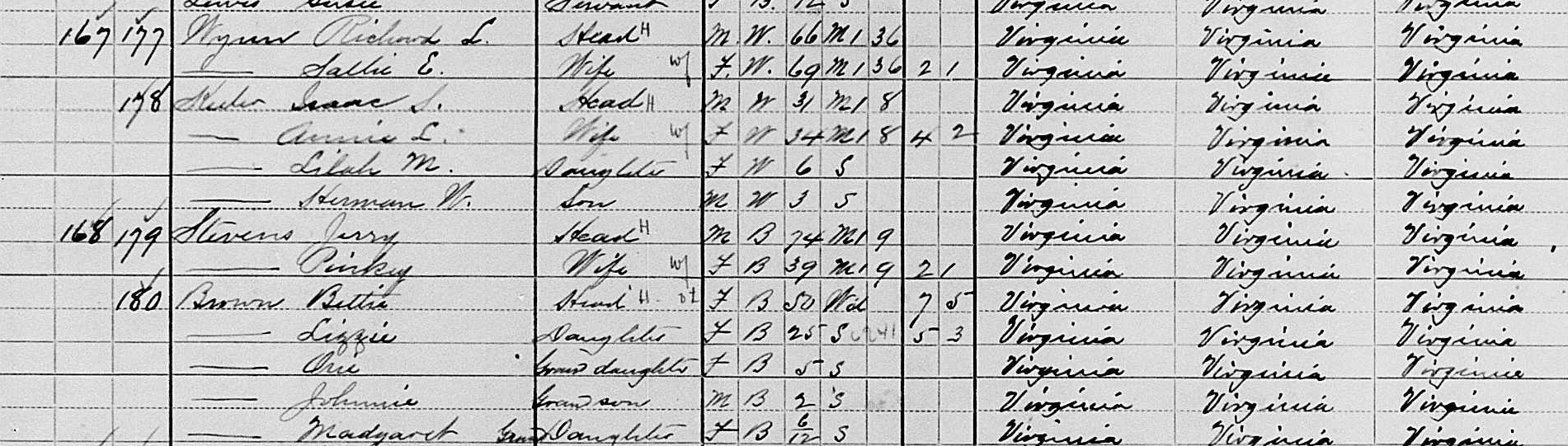

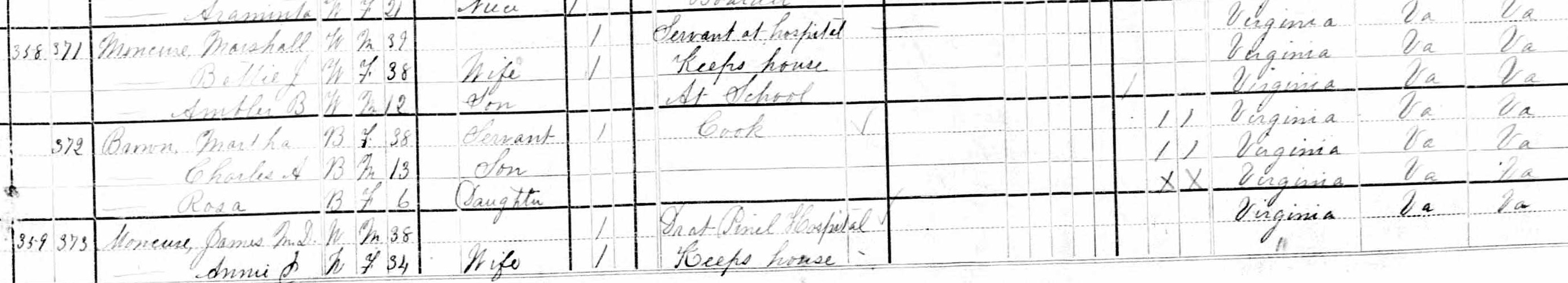

However, a black man named Jerry Stevens was found as a head of household in the same county, but different precinct. He is 74 years old, and living with his 39 year old wife, Pinky! What a hoot! Go, Jerry! Living next door but in the same unit number is a 50 year old widow, Bettie Brown, with her 25 year old single daughter Lizzie Brown, and three young grandchildren with the same last name. Is this Jerry’s daughter and her household? Quite possibly. Of course, they could be Pinky’s sister and family.

However, a black man named Jerry Stevens was found as a head of household in the same county, but different precinct. He is 74 years old, and living with his 39 year old wife, Pinky! What a hoot! Go, Jerry! Living next door but in the same unit number is a 50 year old widow, Bettie Brown, with her 25 year old single daughter Lizzie Brown, and three young grandchildren with the same last name. Is this Jerry’s daughter and her household? Quite possibly. Of course, they could be Pinky’s sister and family.