Last year, at my mother’s funeral, my cousin Jana called me over to her car to present me with a small collection of family things that had belonged to her mother, Ada – who had passed away back in 2009. Some of these items had been made by Ada for our family – beautiful quilts for me and my mother – but other items had been gifted to her or inherited by her long ago. Two small boxes had formerly belonged to Ada’s mother, my great grandmother, Nellie Cox Beyersdoerfer, of Pendleton County, Kentucky.

The contents of the boxes were rather undynamic – mostly newspaper clippings, notes, and small cards with envelopes. But two things stood out that enabled me to expound more on Nellie’s story.

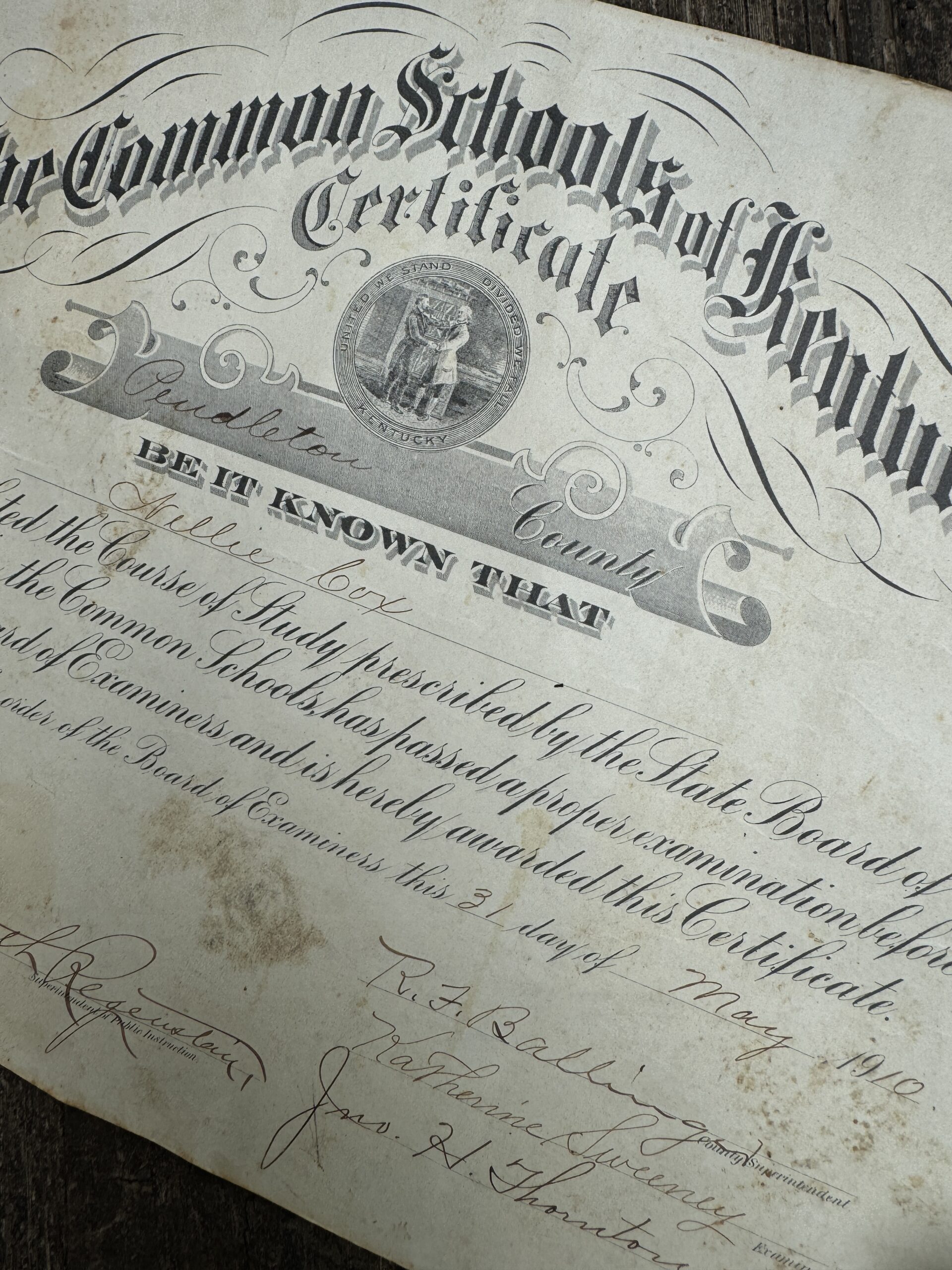

The first item that made me pause was a teaching certificate she obtained in 1910. In the stories my mother had told me about Nellie – or “Ma” as we all called her – she mentioned that Ma had wanted to be a schoolteacher. But in the early part of the 20th century, that was not an easy choice for a single girl. Right out of the gate, her father had already vetoed the idea. He flat out forbade her from becoming a teacher. I suspect one reason for this denial was the lifelong commitment necessary for such a choice. At that time, teachers were not allowed to be married – and had to remain single. My guess is that he knew this choice would not provide the financial and social stability necessary to live on and would result in a very lonely existence. Plus, she was one of the two remaining children he had, and I’m sure they wanted grandchildren.

As far as I knew from the stories, Nellie never made it to becoming a teacher. She met my handsome great grandfather, John Beyersdoerfer, with his dark wavy hair and she was a goner. They eloped to Newport, and the rest was history – hence, our line’s very existence. But this document adds a plot twist for Nellie. She not only went against her father’s wishes, but she did so in a grand and determined manner. She went after her certification – and was successful! This meant testing her way to the piece of paper I held in my hands – a tangible expression of female rebellion! Go, Nellie!

As far as I knew from the stories, Nellie never made it to becoming a teacher. She met my handsome great grandfather, John Beyersdoerfer, with his dark wavy hair and she was a goner. They eloped to Newport, and the rest was history – hence, our line’s very existence. But this document adds a plot twist for Nellie. She not only went against her father’s wishes, but she did so in a grand and determined manner. She went after her certification – and was successful! This meant testing her way to the piece of paper I held in my hands – a tangible expression of female rebellion! Go, Nellie!

My only remaining mystery is the timing of the certificate. This was issued five years before she married “Pa” – and folks didn’t have long engagements in my neck of the woods. So, what did she do with this certificate for five years? Did her father find out about it and then succeeded in preventing her from teaching? Or did she go teach for a while? She is now on my to-do research list for the surrounding counties to see if I can find any mention of her as a teacher in the local rural schoolhouses of the time. That’s not going to be a super easy task, but I owe her that much – so I’m officially on the hunt – stay tuned.

One other discovery in the boxes provided a secondary potential plot twist for Nellie. Or should I say, an additional clue to a plot twist I already knew about.

Nellie’s line stretches very far back into Kentucky. It’s her 2nd great grandmother’s birth in the Commonwealth that makes me an 8th generation Kentuckian. But it’s also that grandmother who (I believe) accounts for our one percent of African DNA that showed up in my test results. For those of you rolling your eyes at holding any value for a one percent result, I really hadn’t credited it either until I discovered documentary evidence that pointed me to a certain ancestor. I uncovered evidence that her family was legally known to be mixed-race – and with this remaining piece of paper, another puzzle piece may have fallen into my lap.

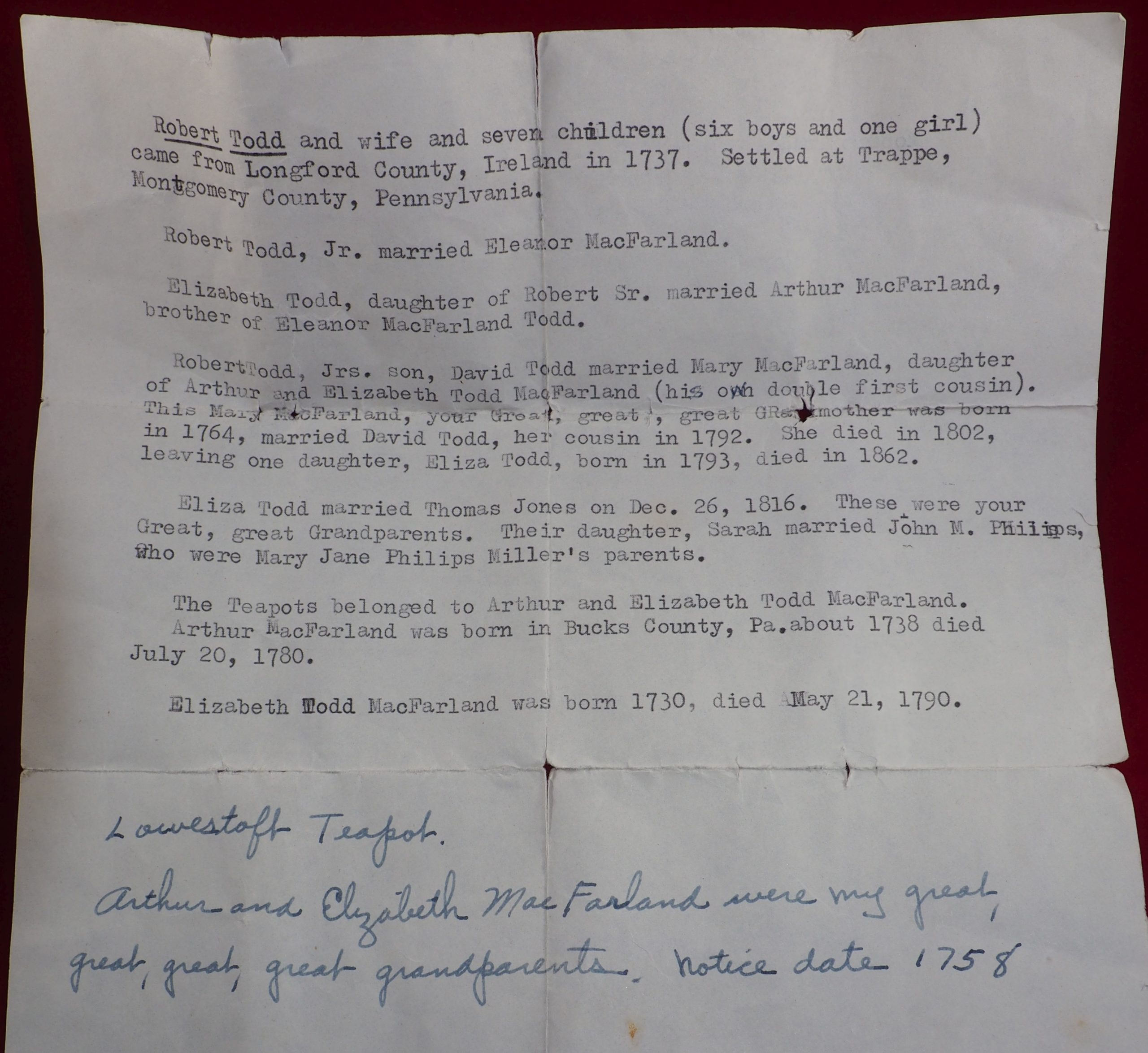

Ironically, I had seen this piece of paper before in my great aunt’s things and made a photocopy of it decades ago – simply because I thought it was neat. At my current stage of family research, this item now holds much more significance.

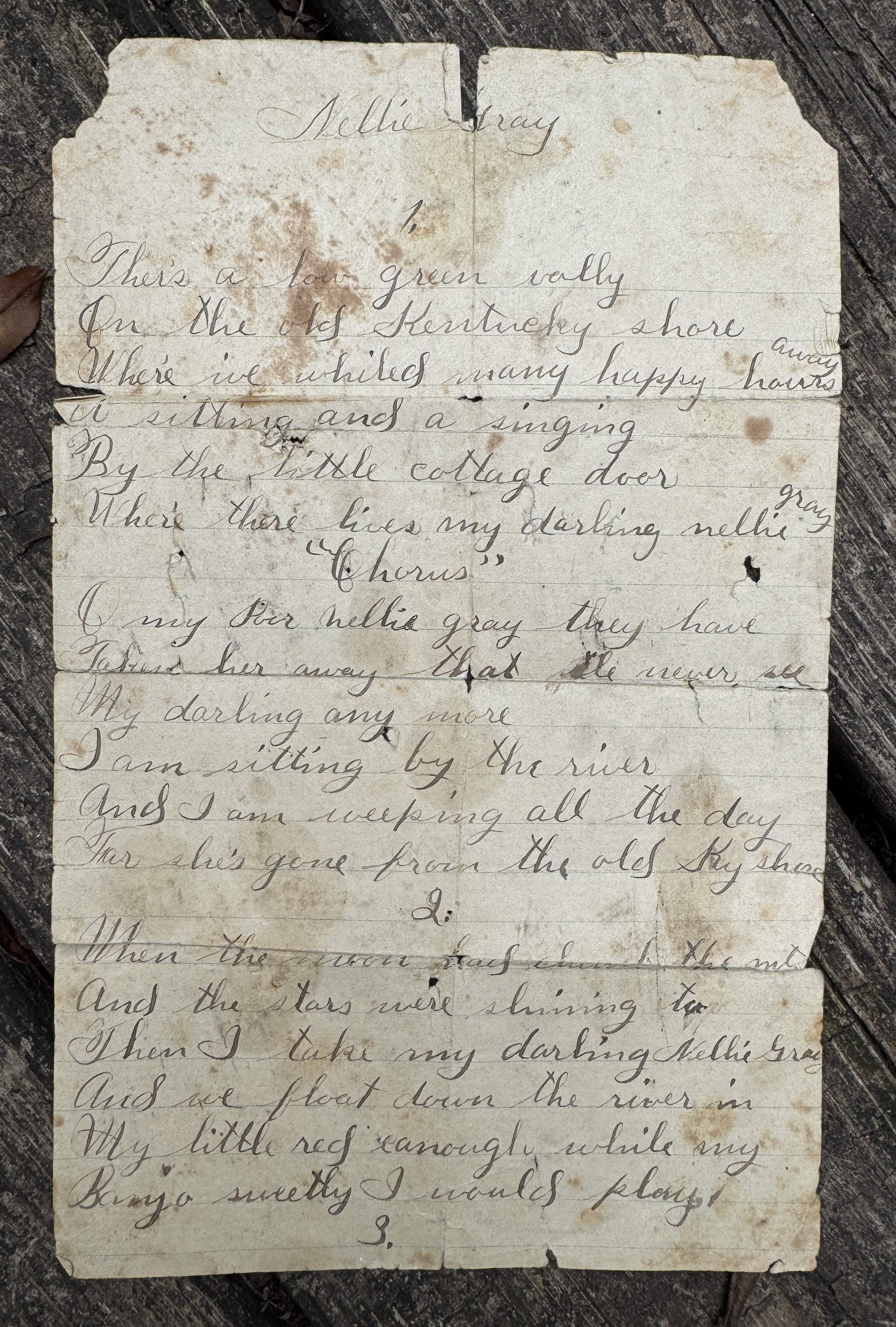

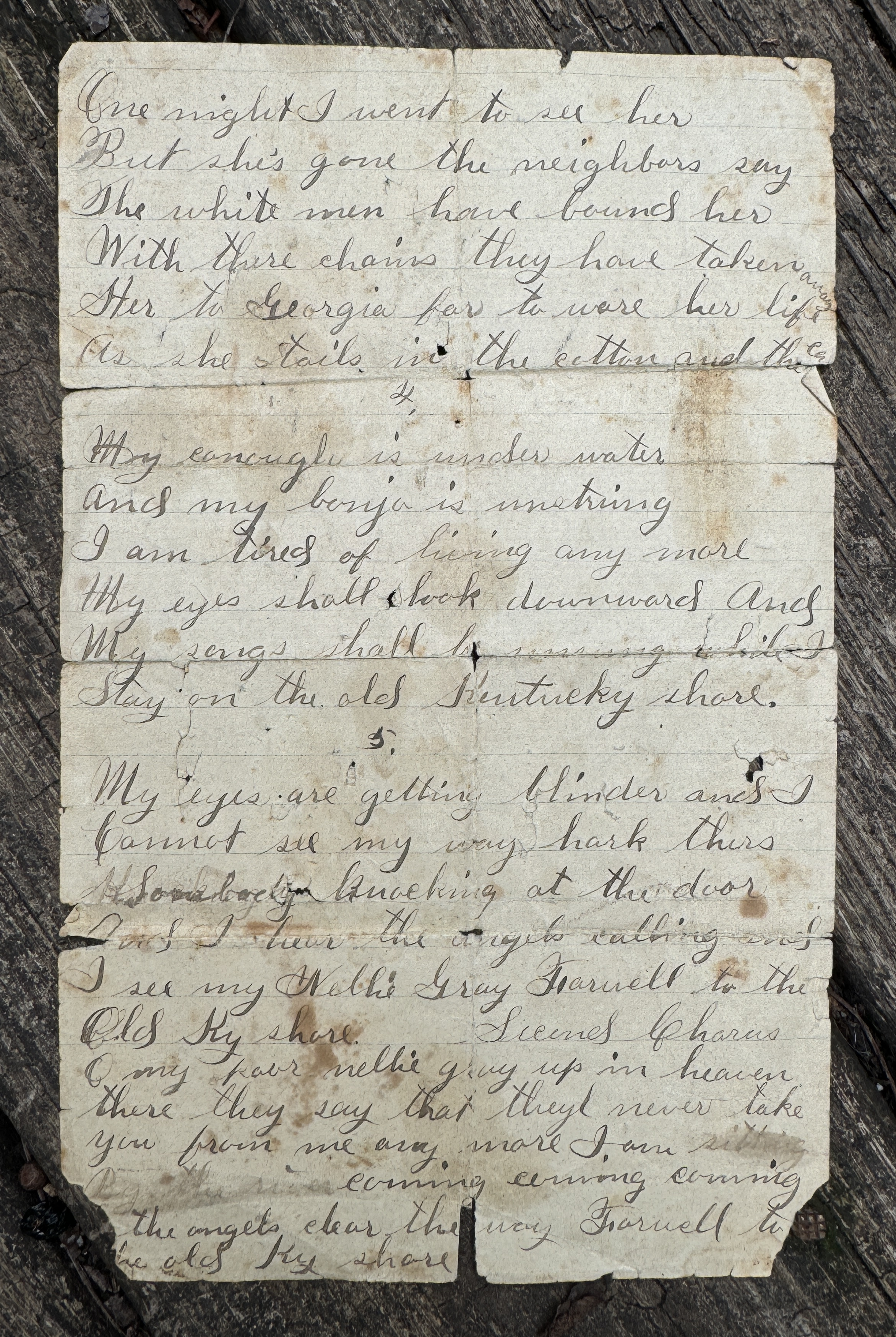

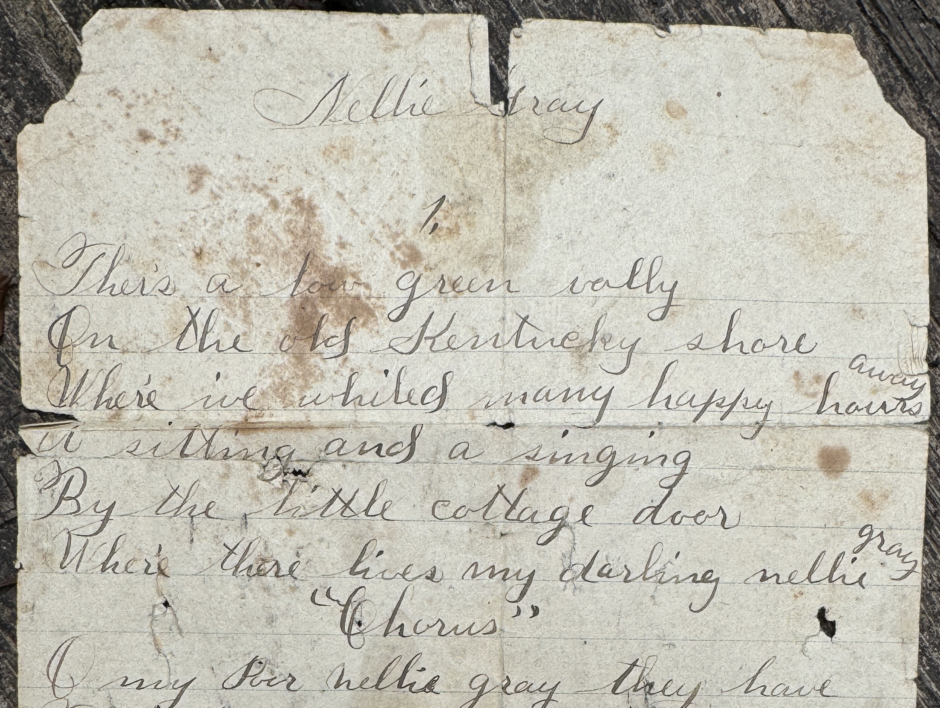

The paper itself is notebook lined, but very old – for context, lined paper was invented as early as the 1770s. It is very dirty and worn – not quite falling apart at the seams, but very nearly. The writing is in ink – appears to be iron gall, which was in use from the 5th century to the early 20th century. For an added element of context, my great grandmother was born in 1891.

The paper itself is notebook lined, but very old – for context, lined paper was invented as early as the 1770s. It is very dirty and worn – not quite falling apart at the seams, but very nearly. The writing is in ink – appears to be iron gall, which was in use from the 5th century to the early 20th century. For an added element of context, my great grandmother was born in 1891.

Upon this very worn piece of paper is written the lyrics to the song, Darling Nelly Gray. While that is a fun coincidence, a song with Nellie’s name – further research into the origins of this song gave me pause.

This song, written by Benjamin Russell Hanby in 1856, told the story of an enslaved man in Kentucky, whose sweetheart was just sold south, never to be seen again.[i] Hanby wrote the lyrics while he was in Ohio – and very much a part of the Abolitionist movement. Its favorable reception in the region led to it being added to the arsenal of nationally popular music to sway public opinion. It was also said that the Hanby family was involved in the Underground Railroad – and the background story for the song came from an escaped slave.

All fiction aside, the theme is steeped in well-known facts for the Ohio River Valley. Without revealing my 2nd great grandmother’s full identity, she came from a family who settled within a known free community of color in Northern Kentucky. This region had been rather liberal in their treatment of different races – up until things got socially worse. By the 1830s, instead of embracing the abolitionist movement across the river, the local factions became hostile towards these opposing viewpoints. So much so that many families relocated out of the area to not only better align with their belief systems, but to remain safe. Just ask John G. Fee what life in Northern Kentucky was like in the 1830s.[ii]

All fiction aside, the theme is steeped in well-known facts for the Ohio River Valley. Without revealing my 2nd great grandmother’s full identity, she came from a family who settled within a known free community of color in Northern Kentucky. This region had been rather liberal in their treatment of different races – up until things got socially worse. By the 1830s, instead of embracing the abolitionist movement across the river, the local factions became hostile towards these opposing viewpoints. So much so that many families relocated out of the area to not only better align with their belief systems, but to remain safe. Just ask John G. Fee what life in Northern Kentucky was like in the 1830s.[ii]

By the late 1830s, my 2nd great grandmother moved across the river, into Ohio, to live with one of her sons who had already settled there with his wife and children. Her other son stayed in Kentucky with their father, and our branch descends from him. Was this move due to illness or changes in local attitudes?

The written song lyrics discovered in my great aunt’s belongings are not entirely unique for the area simply because this song became popular among minstrel and vaudeville troupes well after the Civil War – into the early part of the 20th century – including an evolution into “blackface” performances.[iii] Plus, with the story taking place in Kentucky, I’m sure there was a bit of fondness for a geographically relatable topic.

But knowing our family history and seeing the worn nature of this written note – which appears to pre-date Nellie’s birth – I can’t help but look upon it as a potentially important piece of family history. The social type of family history – the pieces that weren’t supposed to survive, and yet did. While my great grandmother was excellent at keeping the family photos in a safe place, she had very little written items that got passed down. But somehow, this old, worn little piece of paper, containing the lyrics of a well-known abolitionist tune survived. Was this simply a cultural inspiration for her name choice? Was this something sung to her in her youth by a sweetheart? Was this something passed down through her mother’s family that led back to a generation when the shade of their skin was problematic? Meh – maybe it’s just a coincidence?

_____________________________________________________

[i] “Darling Nellie Gray (song),” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, accessed July 31, 2024, https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/2596.

[ii] “Fee, John Gregg,” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, accessed July 31, 2024, https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/300004113.

[iii] “Darling Nelly Gray,” Voices Across Time Database, University of Pittsburgh Library System, accessed July 31, 2024, https://voices.pitt.edu/TeachersGuide/Unit%203/DarlingNellyGray.htm.

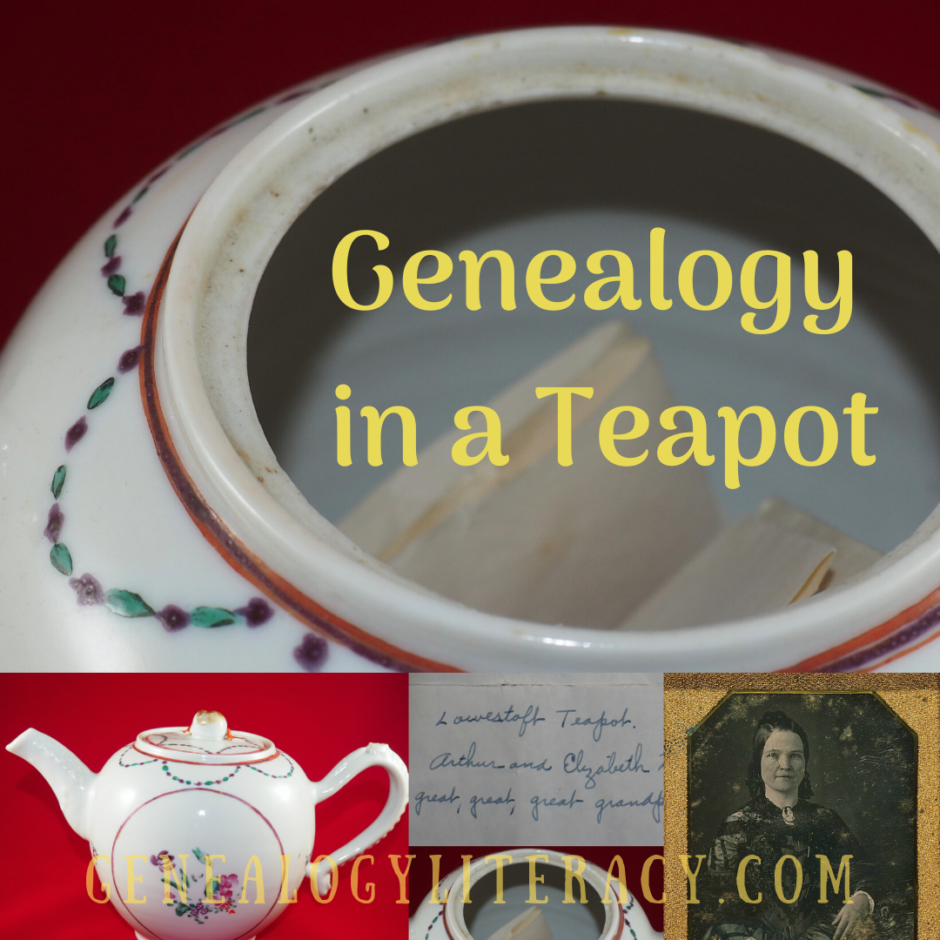

After completing my obligatory happy dance at such a discovery, I got serious about matters and inquired further with the seller concerning the provenance. After all, I was afraid this person was parting with a family heirloom. On the contrary, while it had belonged to his mother’s estate, she had purchased it years ago at a Church rummage sale next door to a nursing home in Florida. A bit of a relief, but still sad, nonetheless.

After completing my obligatory happy dance at such a discovery, I got serious about matters and inquired further with the seller concerning the provenance. After all, I was afraid this person was parting with a family heirloom. On the contrary, while it had belonged to his mother’s estate, she had purchased it years ago at a Church rummage sale next door to a nursing home in Florida. A bit of a relief, but still sad, nonetheless.

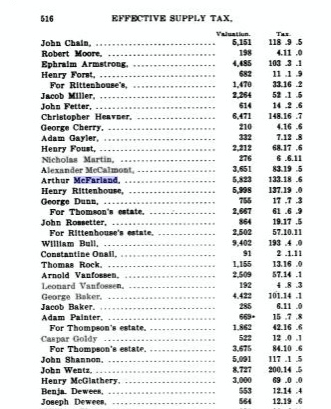

After Elizabeth and Arthur married in 1758, they have four more children. Arthur is listed in the Todd family history as “Major” Arthur McFarland. I have not been able to find record of this military service, but since he was born in 1720 and died in 1780, I’m guessing it’s not for service in the American Revolution. If it was for an earlier war, such as French and Indian, I’d have to keep digging. With a person of property during the Revolution, one naturally questions allegiance, and I’m happy to say that I found Arthur listed in the Philadelphia “Supply Tax” rolls for the year he died. This type of tax was taken from those who were supporting the cause of the Revolution.

After Elizabeth and Arthur married in 1758, they have four more children. Arthur is listed in the Todd family history as “Major” Arthur McFarland. I have not been able to find record of this military service, but since he was born in 1720 and died in 1780, I’m guessing it’s not for service in the American Revolution. If it was for an earlier war, such as French and Indian, I’d have to keep digging. With a person of property during the Revolution, one naturally questions allegiance, and I’m happy to say that I found Arthur listed in the Philadelphia “Supply Tax” rolls for the year he died. This type of tax was taken from those who were supporting the cause of the Revolution. Places like the MET and the Victoria and Albert Museum allow you to search their collections with terms you’ve come across. These are going to be wonderful experts in the matter, even over antiques dealers who might have good intentions, but lack sufficient expertise to get the variances correct. After all, no one is an expert in everything.

Places like the MET and the Victoria and Albert Museum allow you to search their collections with terms you’ve come across. These are going to be wonderful experts in the matter, even over antiques dealers who might have good intentions, but lack sufficient expertise to get the variances correct. After all, no one is an expert in everything.