I could work in the archives for a lifetime and never tire of the treasures they hold. To be blunt, we do not hold them in high enough esteem where our research is concerned. As I go about my daily routine, I sometimes grab enough time to dig for forgotten treasures. Note that I said “forgotten” not “hidden”. They are not hidden – which is an often repeated fallacy about archives, simply because their volume and original state of handwritten creation prevents instant consumption – and yet, not as easily accessed due to their sheer volume, and lack of people to analyze on a microscopic level. Admittedly, some archival collections are hidden, but usually on a temporary basis as staff make their way through the act of processing for responsible access.

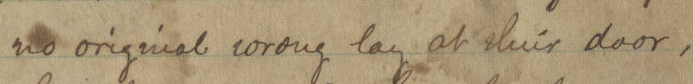

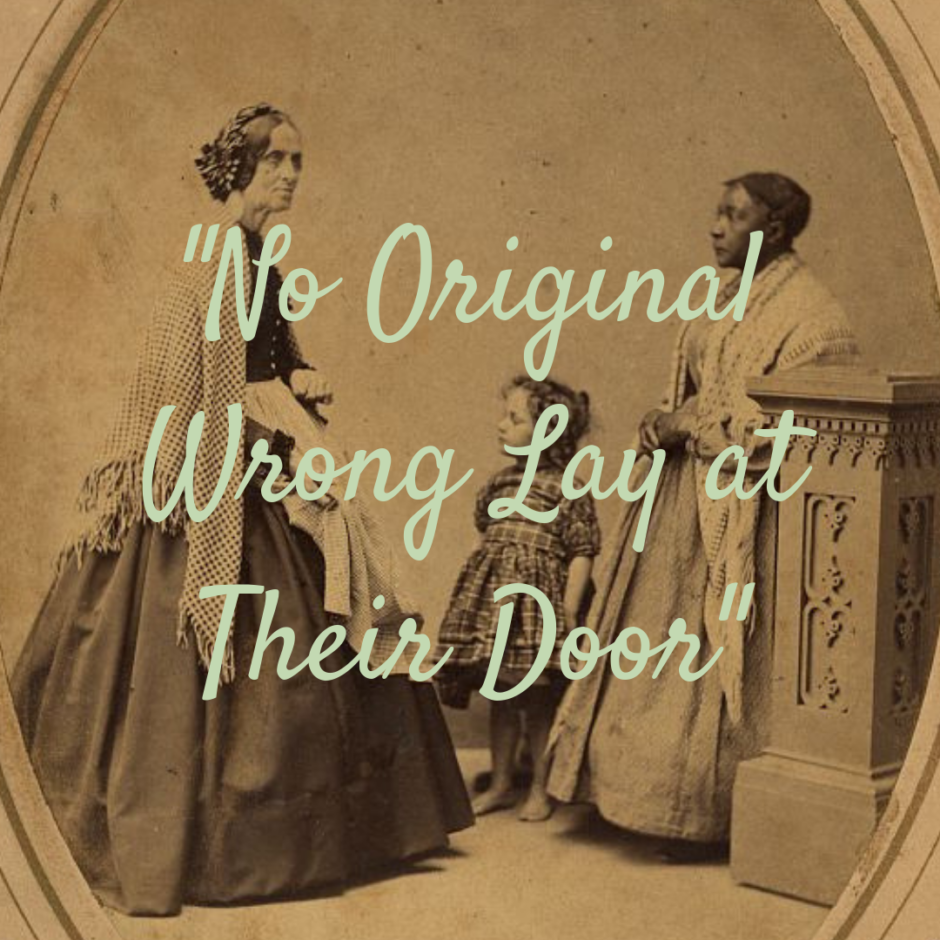

The “forgotten” item I encountered this week was serendipitous, simply because I discovered it while looking for something else entirely – this often happens in the archives, BTW. We begin looking for one thing, and have a really hard time getting there because of all the gems we find littering the path to our goal. The item being sought was a Civil War Diary. While I love a good CW diary as well as the next researcher, I was actually looking at the original to compare to a transcription I discovered in our uncatalogued portion of the library. You know, standard librariany duties. As I was reading the first page of the digitized original, assessing the narrative in relation to the description and scope notes (archivist lingo) – a phrase leapt off the page and stayed with me all weekend: “No original wrong lay at their door”.

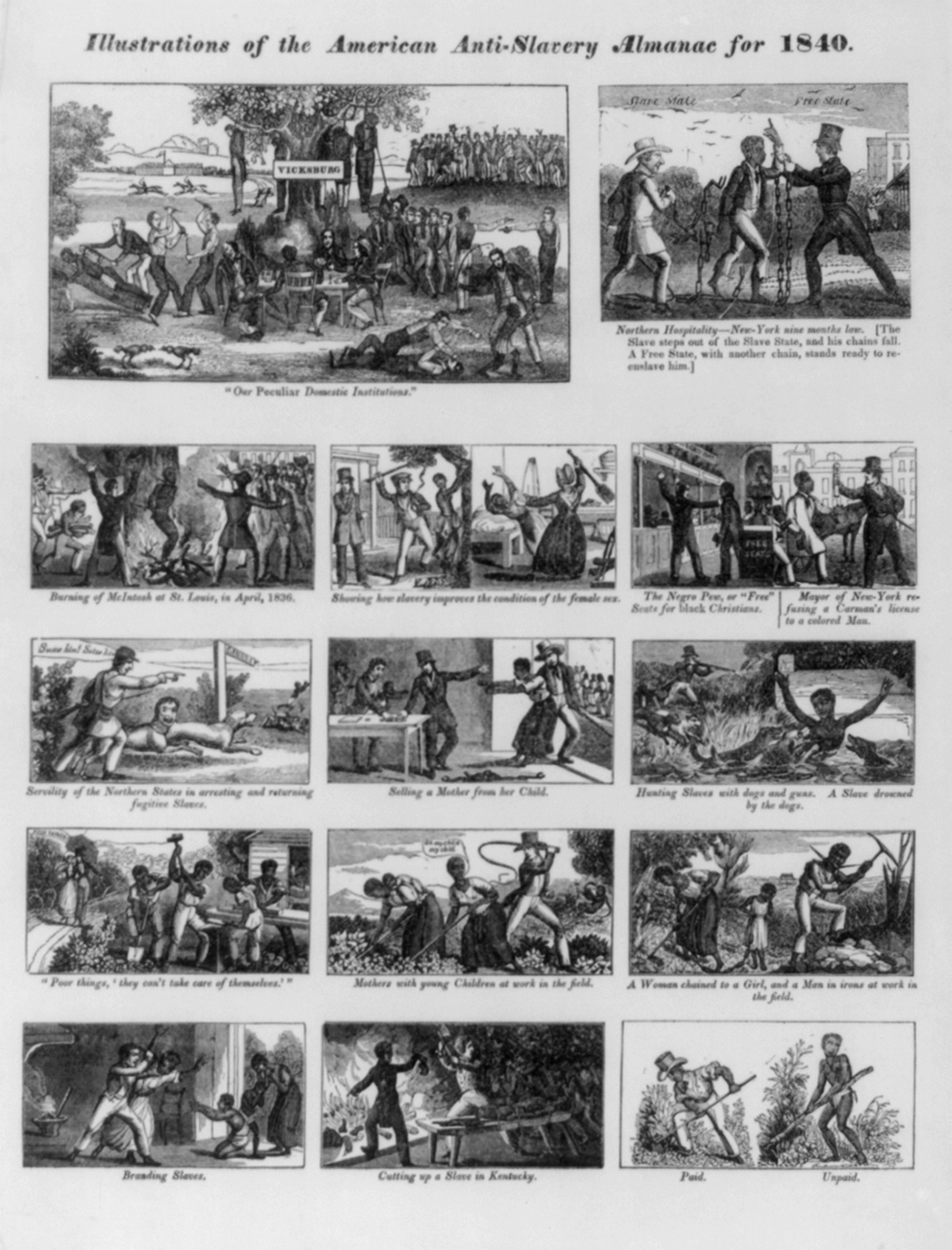

The reason this phrase has haunted me was because of the author’s intent. The author was a Kentuckian, a Union soldier named John Tuttle, attempting to describe the mindset of southerners when it came to the issue of slavery. In essence, he explained their belief in terms that echoed our own struggle of today regarding the heritage of slavery. As most of us have discovered, our genealogical research often uncovers enslavement in the family tree. So many of us have been cognizant of this terrible chapter, and offered to help unite ancestors with their descendants by way of sharing names of the enslaved that we encounter in the records. I have cheered on this endeavor as a form of healing for our land – going back to the roots, and acknowledging our familial connections to those chapters of terror and cruelty. As a white person, who has discovered both enslaver and emancipator in the family tree, I am encouraged and grateful when those of African American heritage also join the voice of unity in this effort – in many cases, embracing the concept of family – and graciously reminding the descendants of the enslavers that we are not our ancestors, and nor should we carry their guilt.

Which is why this soldier’s words made me catch my breath. When describing the rationale behind fighting to keep the system of slavery in place, it appears that there was no guilt associated with their belief – which was not a complete surprise, in its essence. But this lack of guilt was based on the actions of their ancestors. In his words:

Which is why this soldier’s words made me catch my breath. When describing the rationale behind fighting to keep the system of slavery in place, it appears that there was no guilt associated with their belief – which was not a complete surprise, in its essence. But this lack of guilt was based on the actions of their ancestors. In his words:

“They had been reared and educated in the belief that there was no moral wrong in holding slaves as they did. The slaves had descended to them from past generations and no original wrong lay at their door. Many of them had been sold to them by persons in the north more on account of slaves not being profitable in that latitude as they thought, than from any considerations of philanthropy or humanity.”[1]

So let this sink in for just a minute. Apparently, because the system had been put in place by their ancestors, their maintenance of this system (and fight to keep it in place) was not wrong. He also describes their belief in a paternal relationship – caring for the enslaved in a better manner than freedom would afford. In 2018, we can see the horrific evils in that rationalization that led to hundreds of thousands of deaths throughout the days of slavery and during the bloodiest war of our history. But – can we look at ourselves and find any similarities in that rationalization?

It is a true statement that we are not the generation that enslaved people based on their race. Many lived through the first Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s – not fully understanding that it never really ended. We are merely experiencing a resurgence of the fight against the foundational issues that continue to foster inequality in various ways. Have we grown since the 1960s? Yes, of course we have – but we’re not finished!

I am frequently pained by the hostility I see among our neighbors – our fellow Americans – our family. The fabric of our society is being constantly strained and ripped apart because that fabric is woven from threads of time. Threads of slavery, injustice, cruelty, prejudice, racism, hatred – interwoven with threads of emancipation, justice, love, inclusion, equality, freedom, family connections, and most importantly, DNA. I still believe this fabric is strong, and can withstand the strains of divisive social and political forces.

But this is where I get preachy – in the hopes that we can look inward, to examine closely our own fabric.

We know our trees. We’ve been researching them for years – decades even. When examining the fabric of our family, we understand the complexity of the weave. And even though the guilt of slavery may not be on our generation, if we examine the fabric close enough, we can see the threads of our own guilt. We carry the guilt of our own generation. What does that guilt look like? It looks like apathy. It looks like an oblivious existence of comfort. It looks like trees without diversity – and trust me – if you have no diversity in your tree, you are not searching hard enough, or you are choosing to prune away the uncomfortably branches. DNA is lighting up our trees with colorful leaves that we did not know of, or we chose not to see due to that heavy fabric we kept as a blindfold.

We know our trees. We’ve been researching them for years – decades even. When examining the fabric of our family, we understand the complexity of the weave. And even though the guilt of slavery may not be on our generation, if we examine the fabric close enough, we can see the threads of our own guilt. We carry the guilt of our own generation. What does that guilt look like? It looks like apathy. It looks like an oblivious existence of comfort. It looks like trees without diversity – and trust me – if you have no diversity in your tree, you are not searching hard enough, or you are choosing to prune away the uncomfortably branches. DNA is lighting up our trees with colorful leaves that we did not know of, or we chose not to see due to that heavy fabric we kept as a blindfold.

Guilt can only be overcome if we make a healthy and conscious effort to change things for the better. We do not have the power to change all of the wrongs in this world, nor in this country, but we have the power of our generation to examine our fabric and think about what makes us tick. What does our tree tell us? Beyond the research, as we are learning from science, even memories of our ancestors can influence the reactions and fears that drive our motivations today. If that is true – then what memories or beliefs influence us in ways that are not healthy for our society? As a prism scatters light, so can these memories and beliefs passed down through teaching or DNA be scattered and projected through our own lives. In many cases, we don’t realize how much we are influenced by the past generations – even those we have never met.

When I think back about my own childhood, and the things I witnessed from my grandparents and parents, I know that they shaped who I became. And as I learned more, educated myself about diverse cultures and groups – about the fabric of our society, I grew to a place of cultivation. I began ripping out the weeds of their teaching. The weeds or poison ivy of thought that they learned, and passed to me. Do not get me wrong, my grandparents and parents taught me wonderful things, and I admire each and every one of them. But humanity is flawed, and not everything we learn from the previous generation should be honored or allowed to flourish for another generation. It’s time to weed some of those things that make us hesitant to reach out and make things better.

So, why am I writing this to a genealogy audience? Because I firmly believe a huge portion of the power to change lies in our hands. The more the records and spit connect us, the more we can start acting like family. If a member of your family is mistreated, how quickly do you come to their defense, to help them achieve justice? Pretty darned quick. As we come to the realization that we are all family, and as we strive to share this concept with those who care nothing for genealogy, we lead them toward empathy, compassion, and reconciliation.

I am also increasingly disheartened by the low numbers of white folks attending programs or sessions presented on African American genealogy/history – and other non-anglo based classes for that matter. It is shameful how few attend these wonderful classes. Go ahead and tell yourself that you don’t attend because it doesn’t apply to your research or ancestry – go ahead – just try. Because that doesn’t wash! If your ancestors were here beyond one generation, let alone before the Civil War, your family was a part of that history. What if you can’t find a slave owner in your tree? Congratulations, but did your family benefit from the slave economy? Of course they did. That network/system was in place for generations, and your ancestors were a part of it, whether they actively traded in human flesh as a commodity or not. They chose a side in the War driven by slavery – do you really think their side of choice was simply due to geography? Of course not – the issues leading up to that war were numerous and important to most. The records used to research enslaved families involved white owner families – so take a positive step and attend more of these sessions! I guarantee you will learn something helpful about your own research, and are sure to learn more about how our families can connect on a deeper level!

I am also increasingly disheartened by the low numbers of white folks attending programs or sessions presented on African American genealogy/history – and other non-anglo based classes for that matter. It is shameful how few attend these wonderful classes. Go ahead and tell yourself that you don’t attend because it doesn’t apply to your research or ancestry – go ahead – just try. Because that doesn’t wash! If your ancestors were here beyond one generation, let alone before the Civil War, your family was a part of that history. What if you can’t find a slave owner in your tree? Congratulations, but did your family benefit from the slave economy? Of course they did. That network/system was in place for generations, and your ancestors were a part of it, whether they actively traded in human flesh as a commodity or not. They chose a side in the War driven by slavery – do you really think their side of choice was simply due to geography? Of course not – the issues leading up to that war were numerous and important to most. The records used to research enslaved families involved white owner families – so take a positive step and attend more of these sessions! I guarantee you will learn something helpful about your own research, and are sure to learn more about how our families can connect on a deeper level!

As speakers and genealogy teachers, we are quick to promote context as a way of understanding our ancestors’ lives and their motivations for life choices. If we continue to preach context and fail to promote digging into African American historical subjects, we are choosing to foster an atmosphere of division. How arrogant are we that we ignore the historical subjects of diverse American groups because we have arrogantly, and erroneously, determined that they do not fit into our family tree?

As speakers and genealogy teachers, we are quick to promote context as a way of understanding our ancestors’ lives and their motivations for life choices. If we continue to preach context and fail to promote digging into African American historical subjects, we are choosing to foster an atmosphere of division. How arrogant are we that we ignore the historical subjects of diverse American groups because we have arrogantly, and erroneously, determined that they do not fit into our family tree?

What else can we do? Well, I’m a Goonie generation, and I continue to say “This is OUR time!” – I love seeing the weaving of new fabric out there among diverse groups in the genealogy world – but we have to increase this effort a thousand fold! It is NOT enough! The good of those who help share the names of the enslaved in blogs and trees are drowned out by those who choose to erase or ignore the names they encounter – simply because, while they will not accept the guilt, they display actions driven by shame. Which is also driven by a romanticized mythology that perpetuates the heinous lie of the perfect or unblemished family tree!

This is OUR time, folks. We can choose to be forces for good in our generational time here on this planet, or we can choose to spread the weeds of division passed down to us. Of all the traditions and sacred beliefs we share across time, from one generation to the next, please do not sacrifice the future of our country on the traditions born from hate and prejudice. Weed our gardens through love and familial restoration. We were handed this society by our ancestors, but it’s our choice how we shape it for the next generation.

[1] Tuttle, John W. John W. Tuttle Civil War Memoir. 1860-1867. (Kentucky Historical Society Archives, Frankfort KY, SC 406), pg. 1(2).

Does her phone call remove my desire to help them? Not really, but it does allow me to analyze their requests with a much more knowledgeable eye. In the new book, Genealogy and the Librarian, there is a wonderful chapter by Katherine Aydelott from the University of New Hampshire, detailing her lengthy correspondence with an inmate, and how she helped him fill in a lot of his family tree – later discovering that they were 8th cousins (pg.203). But even with this rewarding research relationship, she advises that all correspondence should remain professional, and to adhere to your organization’s policies. In my library’s case, our policy clearly states we will not conduct research without pre-payment. Yes, we have bent the rules slightly when someone just needed a small piece of info that was easily provided – which fit well into my previous pattern of helping with one small page of info easily copied or printed out – but her phone call made me realize that even this small tidbit could have serious consequences.

Does her phone call remove my desire to help them? Not really, but it does allow me to analyze their requests with a much more knowledgeable eye. In the new book, Genealogy and the Librarian, there is a wonderful chapter by Katherine Aydelott from the University of New Hampshire, detailing her lengthy correspondence with an inmate, and how she helped him fill in a lot of his family tree – later discovering that they were 8th cousins (pg.203). But even with this rewarding research relationship, she advises that all correspondence should remain professional, and to adhere to your organization’s policies. In my library’s case, our policy clearly states we will not conduct research without pre-payment. Yes, we have bent the rules slightly when someone just needed a small piece of info that was easily provided – which fit well into my previous pattern of helping with one small page of info easily copied or printed out – but her phone call made me realize that even this small tidbit could have serious consequences.