A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Tea Party

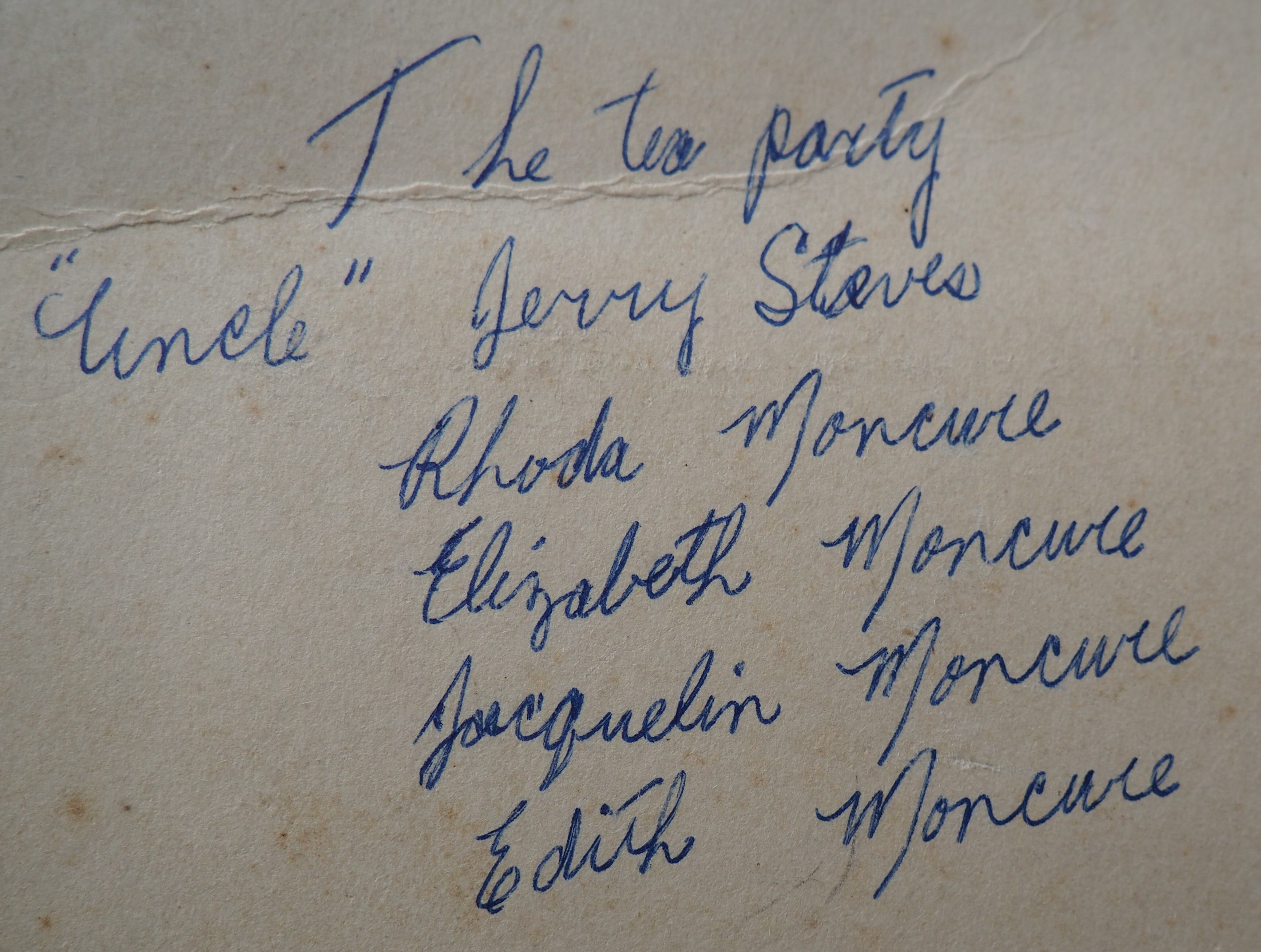

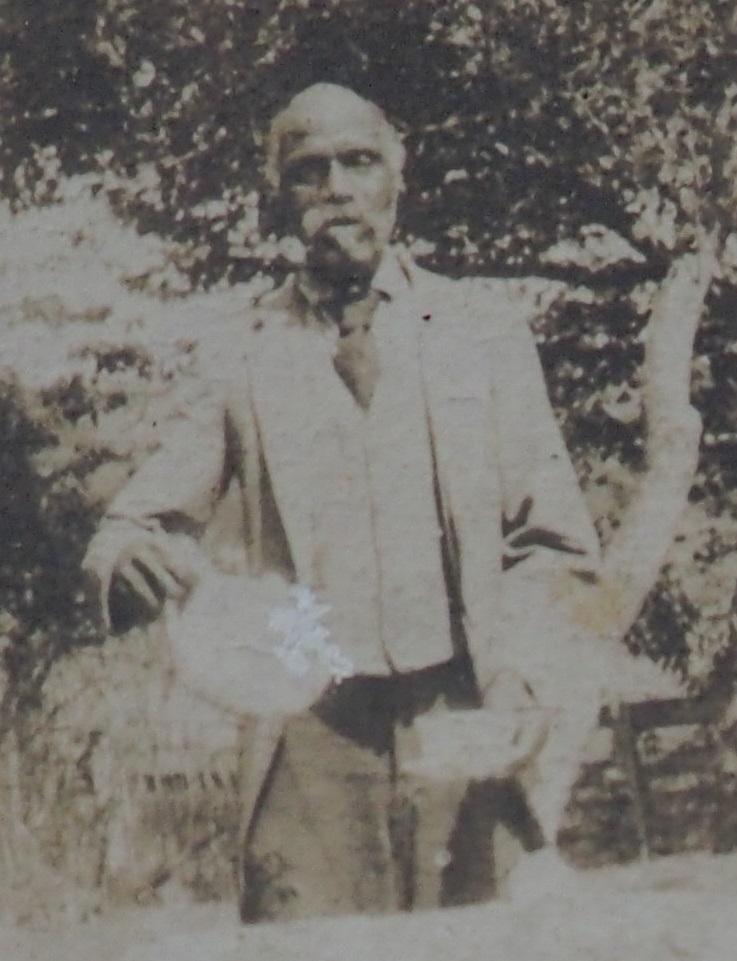

As you may have read in my Preface page, I also blog about tea – usually focused on the equipage necessary to make tea over the centuries (I have a really bad teapot/tea cup addiction) – but often about the tableau settings that demonstrate how tea was presented on a social level. Just last year, I purchased a turn of the century photo that really resonated with me on multiple levels. Not only was this clearly a photo of a “Tea Party” in action, but it was also a southern photo with an uncomfortable tableau. While the tea equipage looked to be in order, large teapot with cups and saucers, the people in this scene presented a remnant tableau of the old south. Even though this was turn of the 20th century (confirmed around 1910) – the white ladies are being served tea by “Uncle” Jerry Steves – a scene reminiscent of southern enslavement. Despite poor Jerry’s continued servitude over 50 years after the end of slavery, the other women were also named on the back, which led to a much larger story – one slightly connected to Kentucky, and the horse racing industry.

The Photo:

Let’s start by analyzing the photo.

The front speaks for itself: Formally attired black ‘servant’ pouring tea for the well dressed white ladies, with two little girls sitting on the ground in front of them. One thing I find to be humorous is the outdoor setting – including: Fancy chairs and table with tasseled rug draping the top, complete with china tea service of some kind. Upon closer inspection, this is not a lush pastoral lawn scene with meadow and garden flowers – oh no – the tiny blades of grass are so sparse that this resembles a dirt side area, complete with chicken running around in the foreground! So, this appears to be somewhat of a faux tableau. Despite their efforts at refinery, it appears that they are having a tea party in a chicken yard – I understand that chickens often roamed around a farm, near the house, and I do see some very tiny blades of grass….but a far cry from their intended luxurious tea tableau.

The back of the photo says:

“The Tea Party. ‘Uncle’ Jerry Steves. Rhoda Moncure. Elizabeth Moncure. Jacqueline Moncure. Edith Moncure.”

Finding the Moncure family:

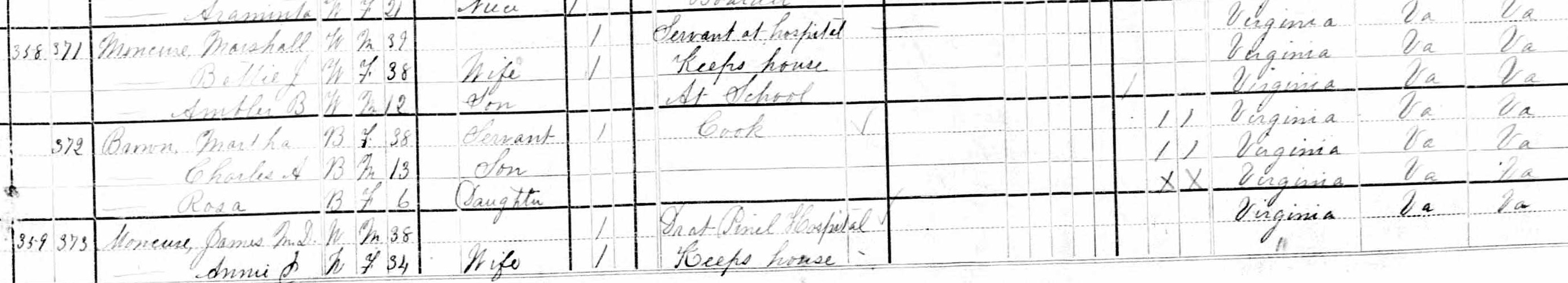

Luckily, this last name, with the family unit containing a Rhoda and Edith, I was able to track them down pretty quickly. In 1910, this household is living together, sans Jerry Steves (I’ll get to him in a second) – but with an additional male, Elizabeth’s son and Rhoda’s husband, Ambler Moncure.

Elizabeth is a widow by 1910, and if you look closely at the children’s ages, Edith is 10 and Elizabeth J. (very likely our Jacqueline) is 6. Does this match the ages of the girls in the photos? Pretty darn close, I’m going to guess more like 1911 or 1912. The hairstyle and dress was my first guess at a year, and I was spot on with census confirmation.

All members of this family were born in Virginia (except for Rhoda as later census records place her birth in Ohio), with this census being recorded in Dinwiddie County. The widowed matriarch, head of the household, Elizabeth is 73 years old.

Looking at Elizabeth alongside Jerry Steves, I guessed they were of similar age. Now, one thing to note right away: The Moncure household had an Irish laborer in the household, but Jerry Steves was nowhere to be seen. Several pages forward and backward did not yield any clues.

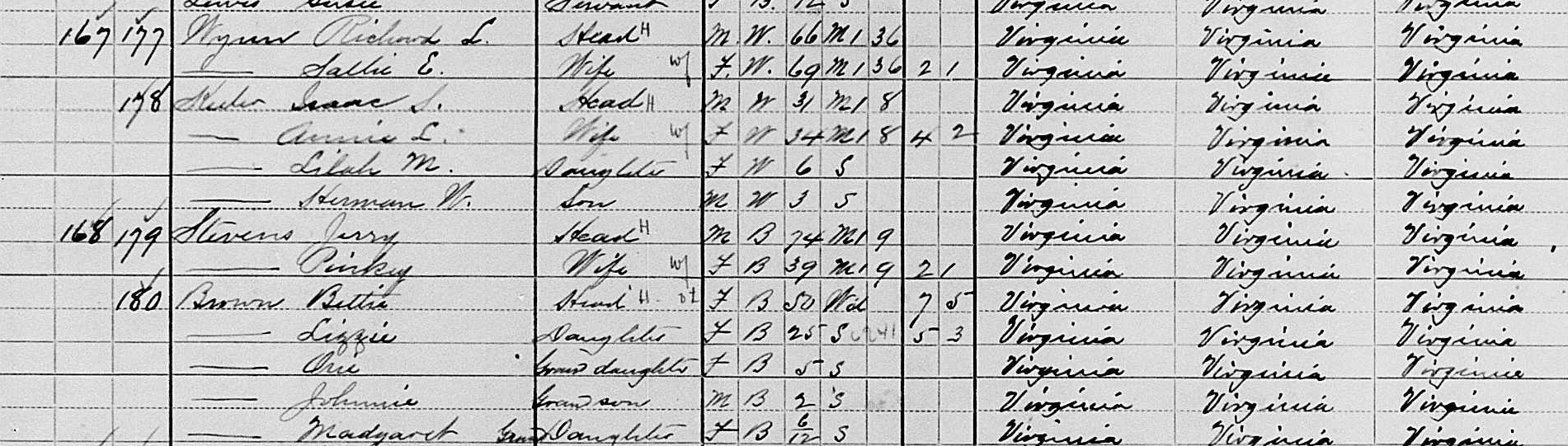

However, a black man named Jerry Stevens was found as a head of household in the same county, but different precinct. He is 74 years old, and living with his 39 year old wife, Pinky! What a hoot! Go, Jerry! Living next door but in the same unit number is a 50 year old widow, Bettie Brown, with her 25 year old single daughter Lizzie Brown, and three young grandchildren with the same last name. Is this Jerry’s daughter and her household? Quite possibly. Of course, they could be Pinky’s sister and family.

However, a black man named Jerry Stevens was found as a head of household in the same county, but different precinct. He is 74 years old, and living with his 39 year old wife, Pinky! What a hoot! Go, Jerry! Living next door but in the same unit number is a 50 year old widow, Bettie Brown, with her 25 year old single daughter Lizzie Brown, and three young grandchildren with the same last name. Is this Jerry’s daughter and her household? Quite possibly. Of course, they could be Pinky’s sister and family.

The most important part of this photo is the fact that this may be the only extant image of Jerry, who was more than likely a former slave as he was born in Virginia (according to this census) in the 1830s. Which is why, after this post, I’m going to contact a local or state archive to inquire about donating the photo. It looks pretty special to me.

Raceland, the Wynns and Moncures:

When looking up the Moncure family in Findagrave, I located a few right away in Dinwiddie County, buried in a family cemetery on a farm/plantation called “Raceland.” Not all of the Moncure family were buried here, but those who entered some of the individuals in Findagrave also posted some links to the other members of the family. This gave me enough of a lead to locate the other members of the Moncure family buried in another local cemetery.

Here’s where history got creepy really fast. With this connection to Raceland, I did a simple Google search for Moncure + Raceland + Virginia = and bingo, some really cool pieces popped up – including a blog post by a former KHS colleague, Tim Talbot, written THIS YEAR! Cue the Twilight Zone music, because I ain’t done yet!

Tim did a lovely job filling in the backstory about the Wynn family who owned Raceland more than likely prior to the turn of the 19th century. To quote the historical marker at this site – BTW, the house still exists – the land and dwellings were developed as early as 1750.

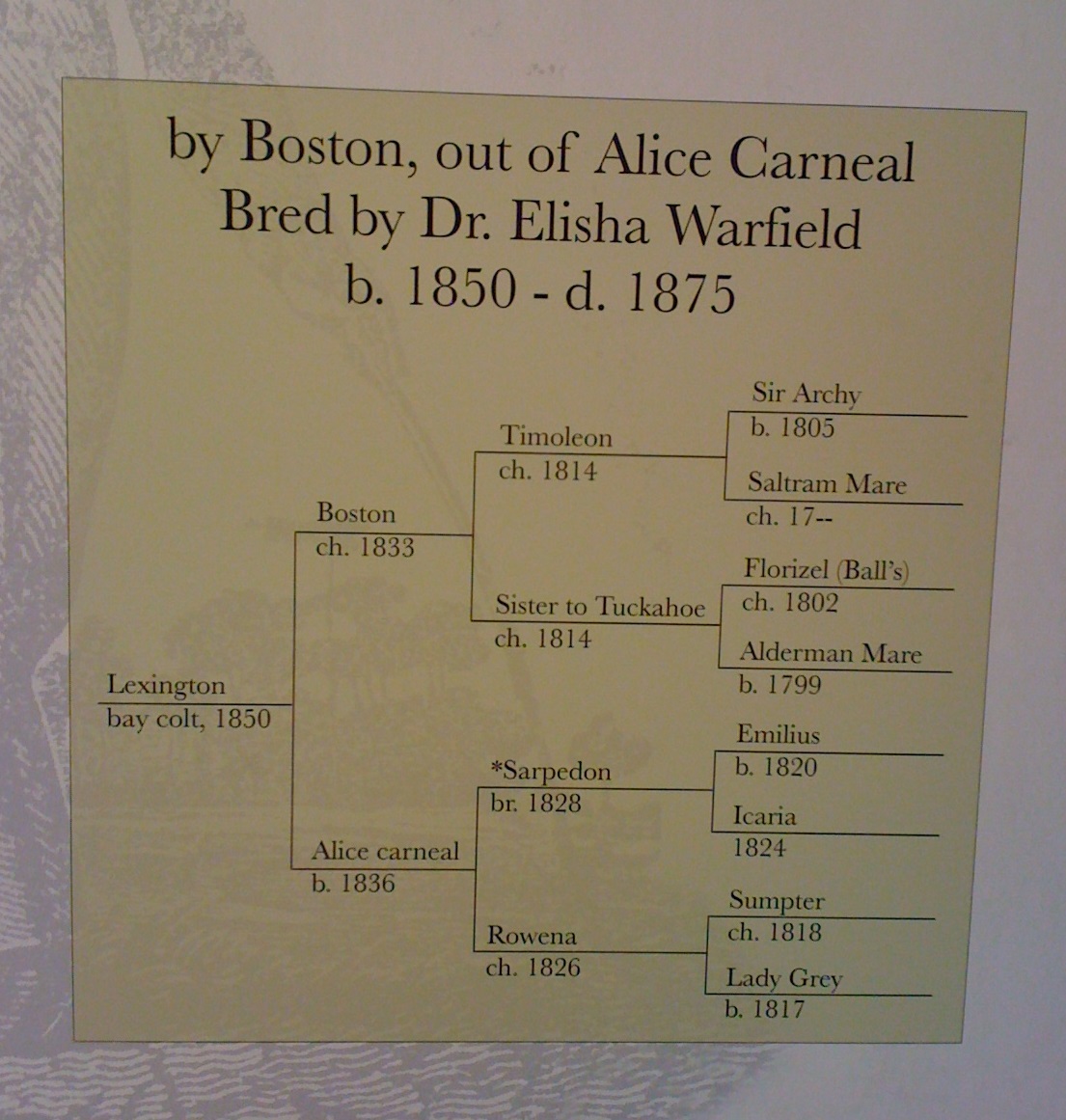

One of the earliest Wynn family members to own Raceland was William Wynn who was known for his horse racing acumen. According to Tim’s blog, William Wynn owned the racehorse, Timolean, who later sired Boston, who was the sire of Lexington, the famed racehorse of Central Kentucky who became the patriarchal line of most modern thoroughbred pedigrees. I am even more familiar with this horse because of a family connection to a historic property we had been trying to save in Cynthiana, Kentucky – who would have thought that this one photo of a tea party would connect me back to the genealogy of a most famous Kentucky horse?! Huzzah!!

Some side notes:

Tim relates that the Wynn plantation was sold to the Moncure family (Marshall Moncure) in 1883, but what he probably did not realize is that Marshall’s wife was Elizabeth Wynn Moncure – so when it was sold to Marshall Moncure, it was staying in the family through Elizabeth.

A note about the enslaved groups on Raceland – Tim listed the number of slaves owned by the Wynn family over the decades – from 35, to 65, to around 38 near the Civil War. Which makes me think more and more about Jerry. With Elizabeth and Jerry so close in age and the label calling him “Uncle” Jerry, I’m going to make a leap and suggest that Jerry was probably owned by the Wynn family prior to the war, and therefore, probably from Raceland.

Of course, I can’t be 100% certain on this summation, simply because there are too many mixed up trees and reports out there regarding which Wynn owned which place – and which Wynn children belonged to which Wynn patriarch – you get the idea. We do know that Raceland was owned by William Wynn, owner of the horse mentioned above. We also know that this William did not stay there permanently, and moved to Arkansas to continue his horse racing endeavors. Somewhere in this timeframe, John Wynn became the new owner of Raceland. Tim reports that John was William’s son, which is possible, knowing the birthdate of William (1784) – but other family members out there are reporting that John was a son of Robert – I know nothing about Robert – and so I will leave the sorting out to the descendants.

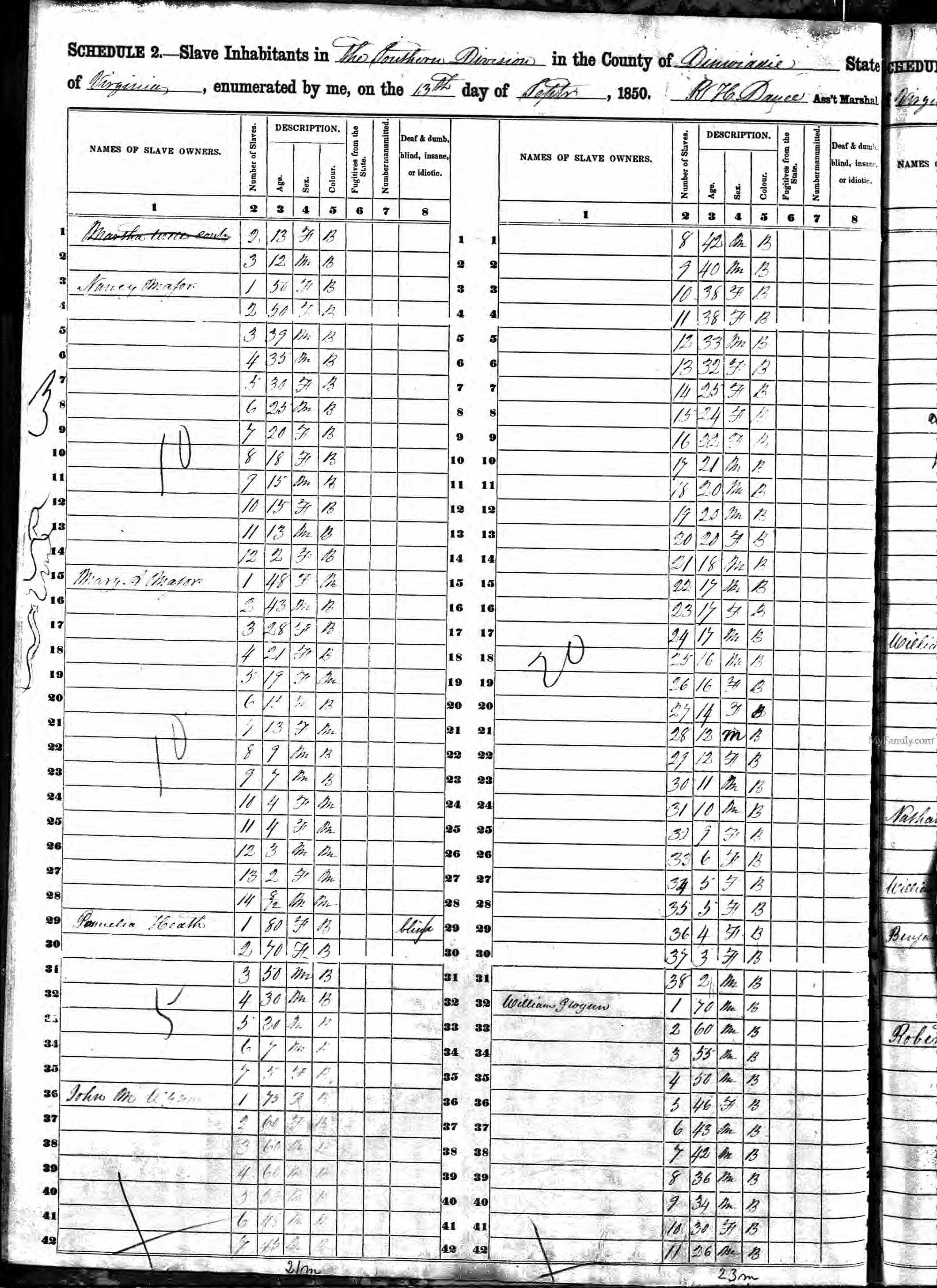

It is clear, however, that John owned Raceland during the pre-War decades, at least according to the historical marker – but did he really? According to the 1860 census, John had no real estate value, although he listed $58,000+ in personal property – most likely a combo of livestock and slaves. Ten years earlier, in 1850, John lists 35 enslaved individuals in his slave schedule entry. But, going back to the 1860 census, a William G. Wynn was living next door to John and his family and listed $215,000 in real estate value along with $53,000+ in personal property. The William living next door was not John’s father as they are too close in age. So, who really owned Raceland? A question to be answered by another researcher.

I was curious as to the enslavement taking place between William G and John Wynn who lived next door to each other. Between the two of them (it should be noted that William also listed a group who had belonged to the estate of Mary Jones) there were 78 enslaved individuals. Drumroll please, did any of the black males in either slave schedule match the age Jerry would have been at the time? Sadly, nope. Jerry should have been 13 in 1850 and 23 in 1860, and the closest I could get in these households were 16 and 26, although, while there isn’t anything close in 1860, there is a 12 year old boy in John Wynn’s household in 1850.

So….why aren’t Jerry’s details matching up?

When reviewing the 1910 census, Jerry was living just two residences from Richard Wynn, who, according to the John Wynn household of 1860, was Elizabeth’s brother. The age in 1910 for that Richard is an exact match.

While it would be convenient to associate Jerry to Richard Wynn, Jerry threw us a huge curve ball:

According to the 1902 marriage of Jerry and Pinky, Jerry gives his name as Jerry Stephens – with a birth year of 1837 and his birthplace as Mississippi – NOT Virginia – even though his birthplace is listed as Virginia (as well as that of his parents) in the 1910 census. As a bonus, he gives the names of his parents: James and Esther Stephens. Pinky’s parents were also included: Abram and Charlotte Coles. Pinky, on the other hand, listed her birthplace as Dinwiddie County Virginia.

In conclusion:

Was the photo taken at Raceland, the residence of the Moncure family? Despite Jerry’s residence elsewhere in the county, did he work there as a domestic – thereby explaining the common, yet pretentious endearment, “Uncle”? Did Jerry happen to work for Richard instead and perhaps the picture was taken at Richard’s house during a visit to Elizabeth’s brother? Pure speculation.

Does Jerry’s birthplace indicate that he had no pre-war connection to the Wynn family? Quite possibly. However, let us not forget that slave sales extended beyond borders, and Jerry’s presence could be a matter of pre-war sale happenstance. Also, remember, that the Wynn family relocated to Arkansas, and based on a couple of others buried at Raceland, the family members did travel back and forth between these states. Jerry could have been an acquisition during those years – OR – was he, instead, connected to the Moncure family?

This family also owned large plantations in Virgina, and Marshall Moncure’s parents both died in New Orleans (according to a couple of older local history books) – with the Louisiana and Missisisippi slave markets so entwined, we cannot rule out a Moncure relationship for Jerry. It should also be noted that Jacquelin’s name comes from the family name and plantation name associated with the Moncure ancestors – as their number of enslaved workforce had to be huge – they cannot be ruled out as a pre-war connection for Jerry.

It is tremendously sad that Jerry’s pre-war life is so shrouded in mystery – although, having the names of his parents might help those in further research. Jerry’s roots may be firmly entrenched in Mississippi, and he may only be connected to Dinwiddie County by his new wife. But, remember the Brown household living in the same unit as Jerry and Pinky? As a post script, the 1880 census listed another Brown household living between the households of Marshall Moncure and his brother Dr. James Moncure. Marshall was listed as a servant in the hospital, while his brother James was a doctor there. The black family living between them was the household of Martha Brown, listed as a cook. Does this give us a directional clue as to Jerry’s connection? Again, we cannot say for certain.

I’m hoping someone out there will recognize Jerry Stevens/Stephens and his family (Pinky, James, Esther) – regardless, hopefully, others can resume Jerry’s research after it arrives at a Virginia archive. Once it is placed, I will amend this post to report its final destination.