Repeated Scenario:

Repeated Scenario:- The family passes on the collection to another willing family member who will lovingly continue Matilda’s work, and care for the collection as we all envision.

- A willing family member volunteers to take the collection, in the hopes of continuing Matilda’s work, and it goes in a basement or attic until they retire and can devote sufficient time to its care. However, if this next family member dies before taking on the work, the collection will need to find another home.

- No one in the family wants this, but realizes its value and donates it to a non-profit organization of their choice: Library, historical society, local museum, genealogical society, etc.

- The family members in charge of Matilda’s estate have no clue about the value of her genealogical research and toss the many files of research into a dumpster! Oh, the horror!

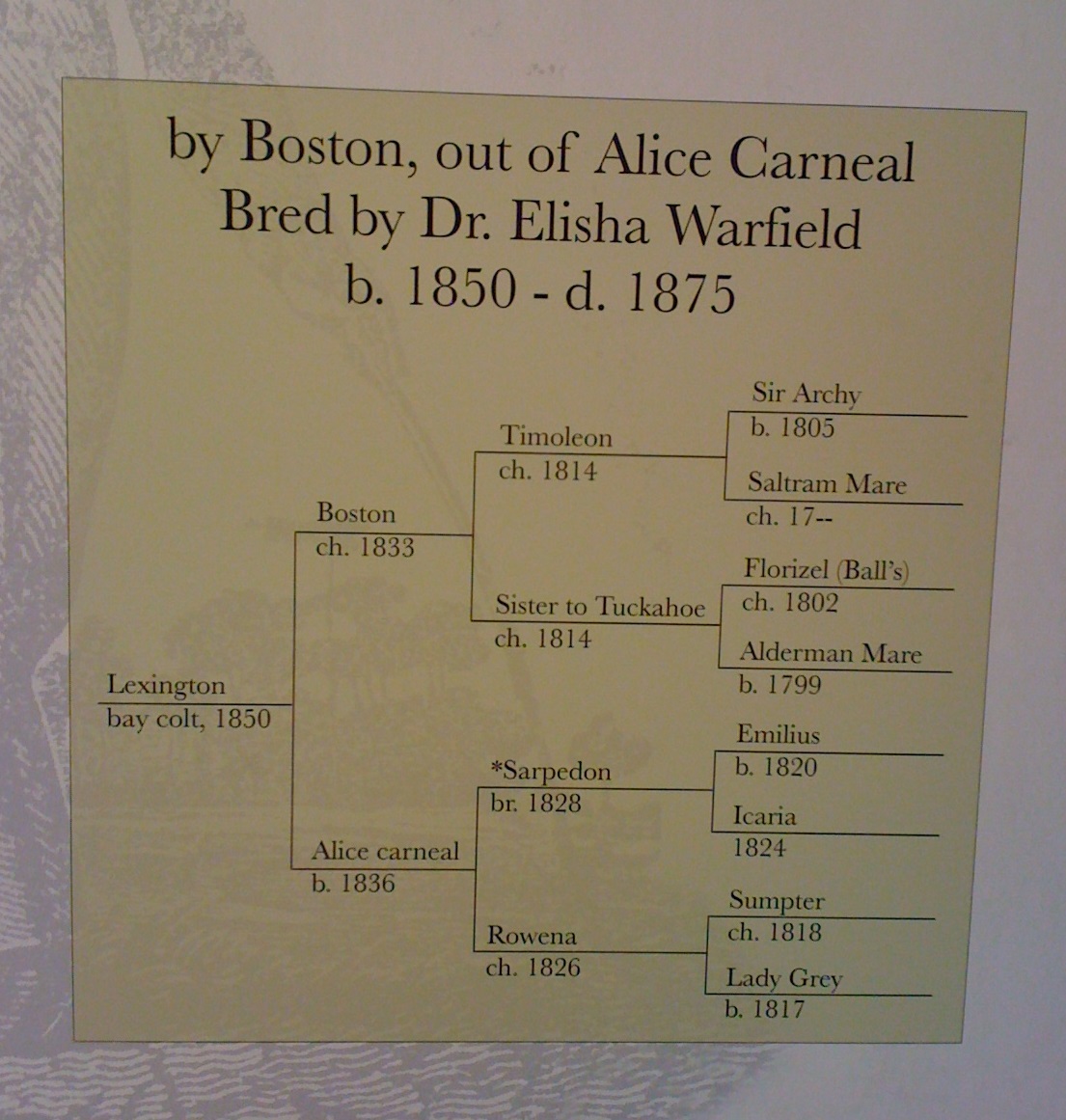

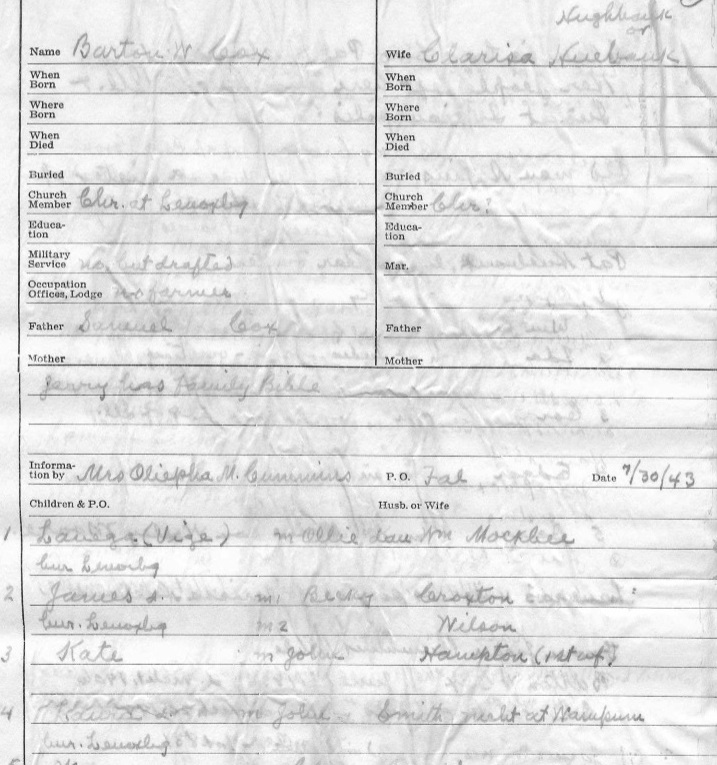

Is there original family material inside? If we find original family photos, correspondence, sourced research reports, bible records, diaries, ephemera, etc…..that’s a home run. We LOVE these components because they are unique, tell a story, and in many cases, fragile. Our facility can preserve them, and make the collection accessible to researchers and many future family members.

Is there original family material inside? If we find original family photos, correspondence, sourced research reports, bible records, diaries, ephemera, etc…..that’s a home run. We LOVE these components because they are unique, tell a story, and in many cases, fragile. Our facility can preserve them, and make the collection accessible to researchers and many future family members.

Point taken – but I’m here to pour a bucket of cold water over your head: Which would you rather have, a research report with full citations donated to a non-profit collection that your family can access for generations – OR – would you rather see your decades of hard work tossed into the dumpster?

Point taken – but I’m here to pour a bucket of cold water over your head: Which would you rather have, a research report with full citations donated to a non-profit collection that your family can access for generations – OR – would you rather see your decades of hard work tossed into the dumpster?- Begin to prioritize. Most genealogy organizational how-to articles will help you organize your research into color coded folders, binders, boxes, cabinets, etc. Forget that for now. Your prioritization should begin with the most important

pieces of your family collection. If you walked into the office/closet during a natural disaster and had to pick one box to take with you, what would it be? If you can’t lay your hands on one to two boxes of original family material or research, you’ve already lost the estate battle.

pieces of your family collection. If you walked into the office/closet during a natural disaster and had to pick one box to take with you, what would it be? If you can’t lay your hands on one to two boxes of original family material or research, you’ve already lost the estate battle. - One way to reduce, as I mentioned earlier, is through citing your sources without keeping a photocopy of the original. I know that makes you nervous, but it’s the goal we should all be striving for in our research. Caveat: The copies I am referring to include items that can be easily pulled up via Family Search or Ancestry, Internet Archive, or Photocopies from other books that are readily available, etc. If you have a photocopy of a record that has never been digitized, and it took a trip to the courthouse to retrieve, by all means, keep that copy. The same goes with family group sheets and family Bible record copies from relatives – these are not things you can cite and find anywhere else (usually) – so retention is a must.

- Photo albums are their own beast: consider decreasing the amount by eliminating images taken of landscapes while on vacation, blurry images, and duplicate images – pick the best – eliminate the rest (of these photo categories).

- Ephemera – While I’m a big fan of ephemera, there should be a limit on what you keep. Travel brochures, postcards with little to no family info, restaurant napkins, matchbooks, receipts, canceled checks, should all be reduced or eliminated unless there is a great story or sentimentality to the item. If you do have a large ephemera collection tied to places over the years, consider pulling those out and donating to an appropriate institution on the collection’s own merit.

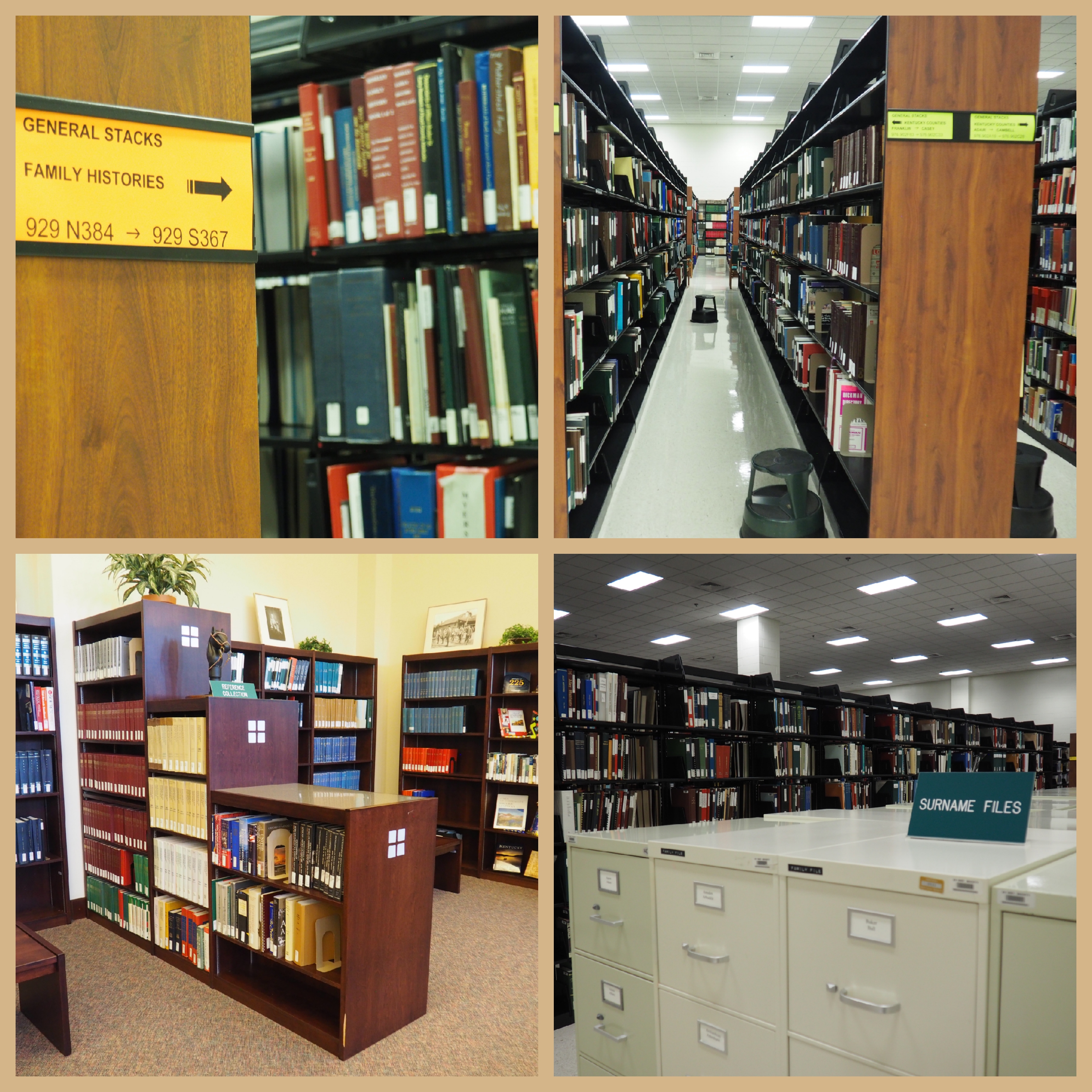

- Always separate publications away from your genealogy collection. Sure, they can be in the same area during your research years, but separate them out during the organizational process. Someday, these can be donated to local libraries, or discarded if there are multitudes of copies already out there – but don’t muddy your genealogy waters with outside, mass produced publications.

On a personal note, my grandmother died a few years ago – but due to the hoarding that went on in that household, unchecked for decades, it took the full 2 years allowed to settle the estate. Even after her house had sold, we were working through the last portion of her belongings that were stored off-site in an environmentally secure storage facility. Up until the very last hours, going through that last batch of family significant items, the sheer volume of “things” and lifelong remnants was mentally and physically exhausting.

- Once you have prioritized the most important sections of your collection, go through them with a fine toothed comb of analysis. Label all of the photos. Re-house the important documents and photos into archival safe folders and boxes (this is also a nice way to differentiate between the important and less important segments).

- For each box of documents related to a surname or family, write a research report that fits into the first folder – serving as a family introduction to what’s inside and where this collection fits into the family history. This is your opportunity to use the citations I mentioned earlier – but in smaller reports that do not seem as daunting. Include photos of heirlooms in the report to connect them in family context. You can keep these electronically active as you research, updating them periodically, and placing an updated version of the report in the file every year or 6 months depending on the research activity for that branch.

- Think about the odds of the entire collection surviving – and then explore ways of sharing copies of the history. The more copies that exist out there, the better the chance of connecting to future researchers: Making a photobook history through the many self publishers out there. These books come in slick professional looking products that your family will love to pass on as important keepsakes. Also, if you don’t plan on donating the entire collection to an organization, make copies of the research reports or photobooks you wrote and donate to local libraries and museums – this allows them to survive on file for researchers.

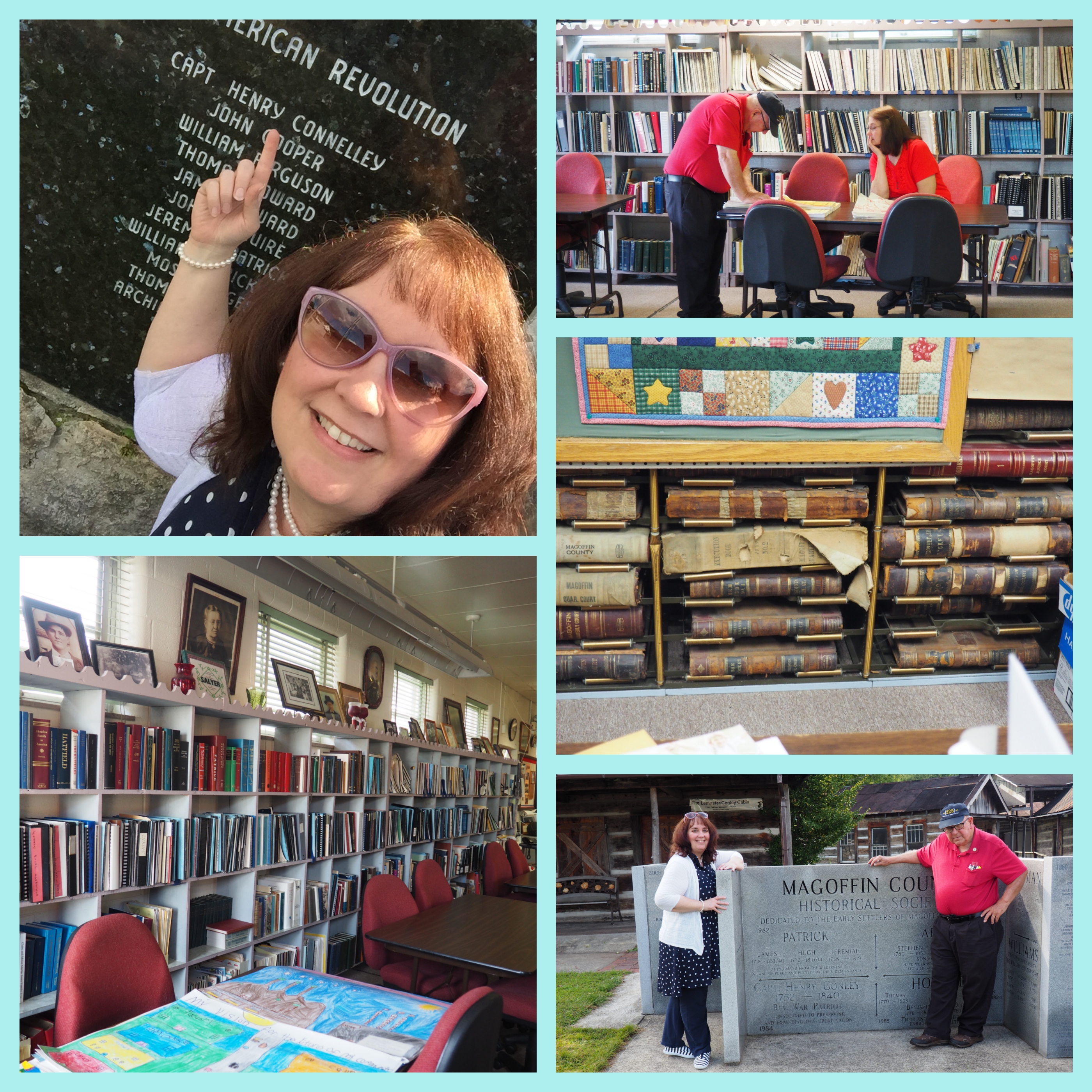

- Do you want to donate the collection you just put together? Consider getting advice from a local professional. Contact the museum/library of your choice and ask to consult with an archivist about your genealogy collection. They can advise you on best practices, and whether they would be interested in obtaining the collection – if you already know that they woudn’t be interested, or wouldn’t make a great fit, shop around for a place that does, and then consider estate planning to make the donation a legal agreement. Also, don’t be afraid to ask them about their collection space and future collecting policies – as well as staffing levels – as this affects processing time and the future access of your collection.

- But….you have a different scenario: your research is well sourced, not bulky, but stored neatly as a digital file on your PC or in the cloud. You’ve used a wonderful genealogy software that allows your files to be shared with multiple family members. That’s great! But what happens when the software you are using upgrades after you are gone – and the file can no longer be read – save as a gedcom? Perhaps. But since we cannot see the advanced technological environment coming along, it’s a safe bet to store your reports in multiple formats, including printed reports, and make sure you keep up with best practices of data migration.

I am NOT suggesting that you have to reduce your collection to one box or binder. In some cases, that is not possible – in others, that isn’t practical. However, when we archivists process collections, we are allowed to discard elements that do not fit the collection – categorized as “processing discards” = superfluous papers with duplicate information, blank sheets, commercial (widely published) brochures/publications, damaged elements, etc. Knowing this, you may be tempted to dismiss my entire post – after all, an archivist can process my collection as they see fit after I’m gone. Really? Do you really want the reduction filter to come through someone who does not know your family and related collection?

NO – you want to retain that power and prepare to donate a unique and useful research collection.

Happy Organizing!

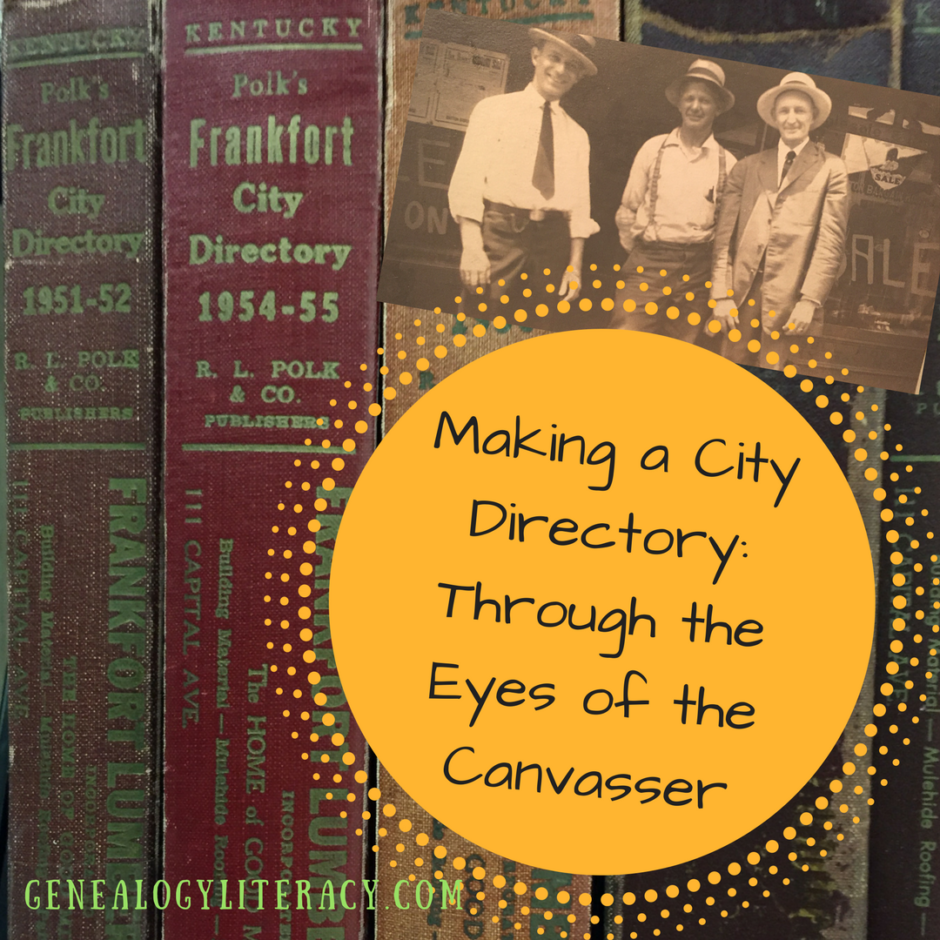

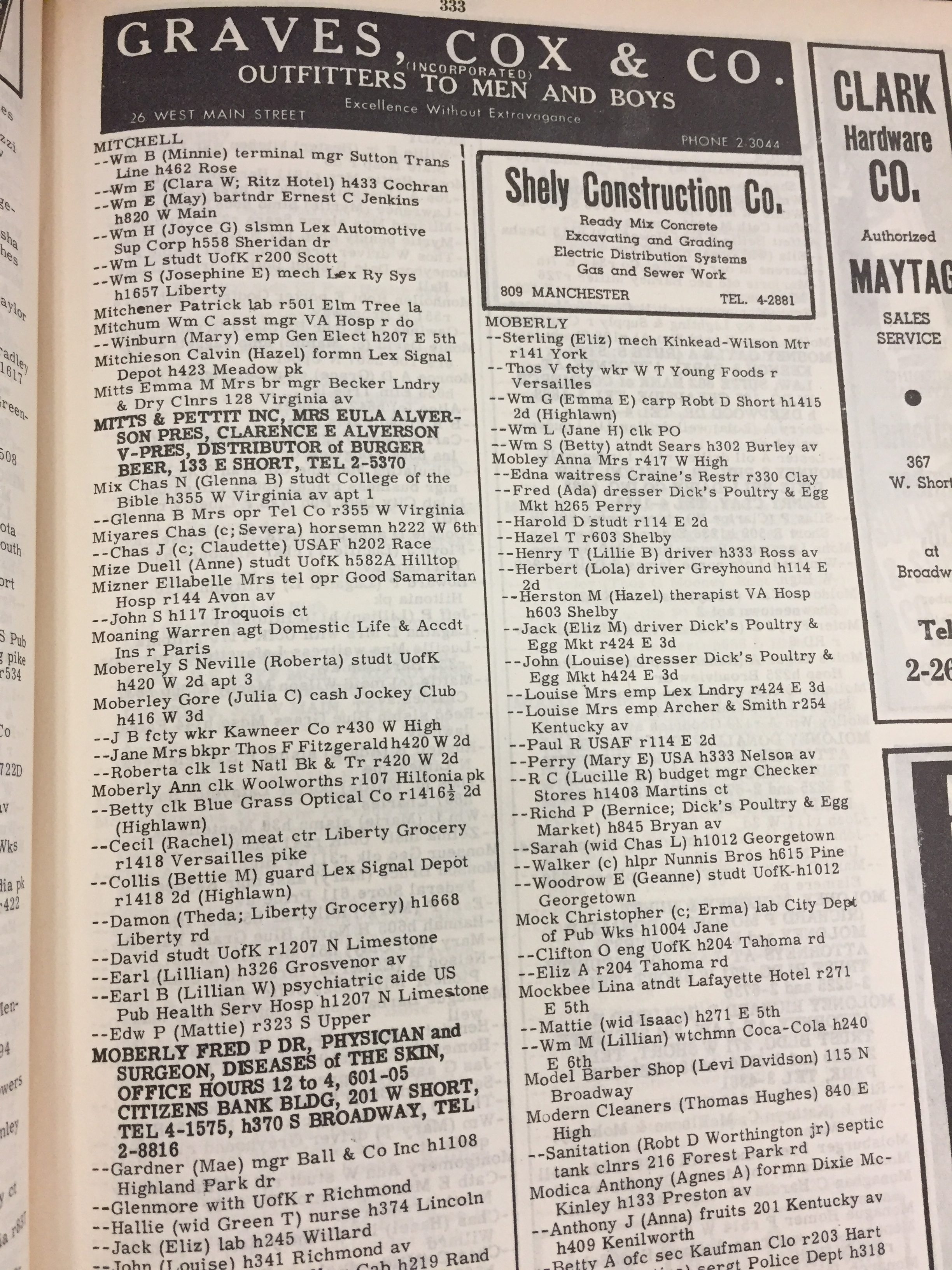

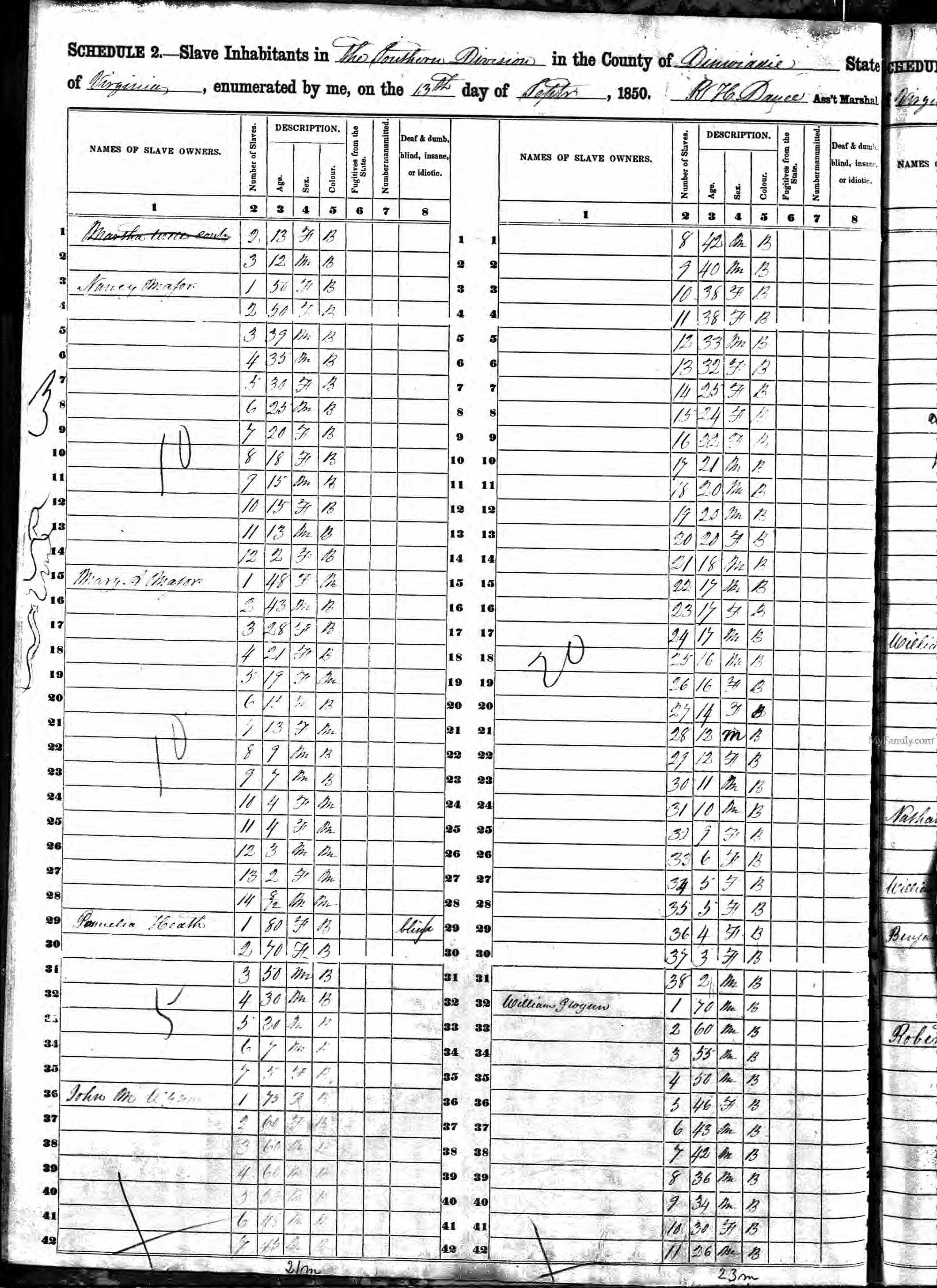

Question: One of our academic researchers was following the life of a single African American woman in the late 19th century. As she turned to City Directories to track residences over the years, she posed a question to us regarding the creation of these directories. She wanted to know who was included in these yearly guides. Obviously, not an entire household, but not always the head of household either. Was everyone included in a City Directory or did you have to pay to be listed? After all, these were valuable resources for advertising your business during that time.

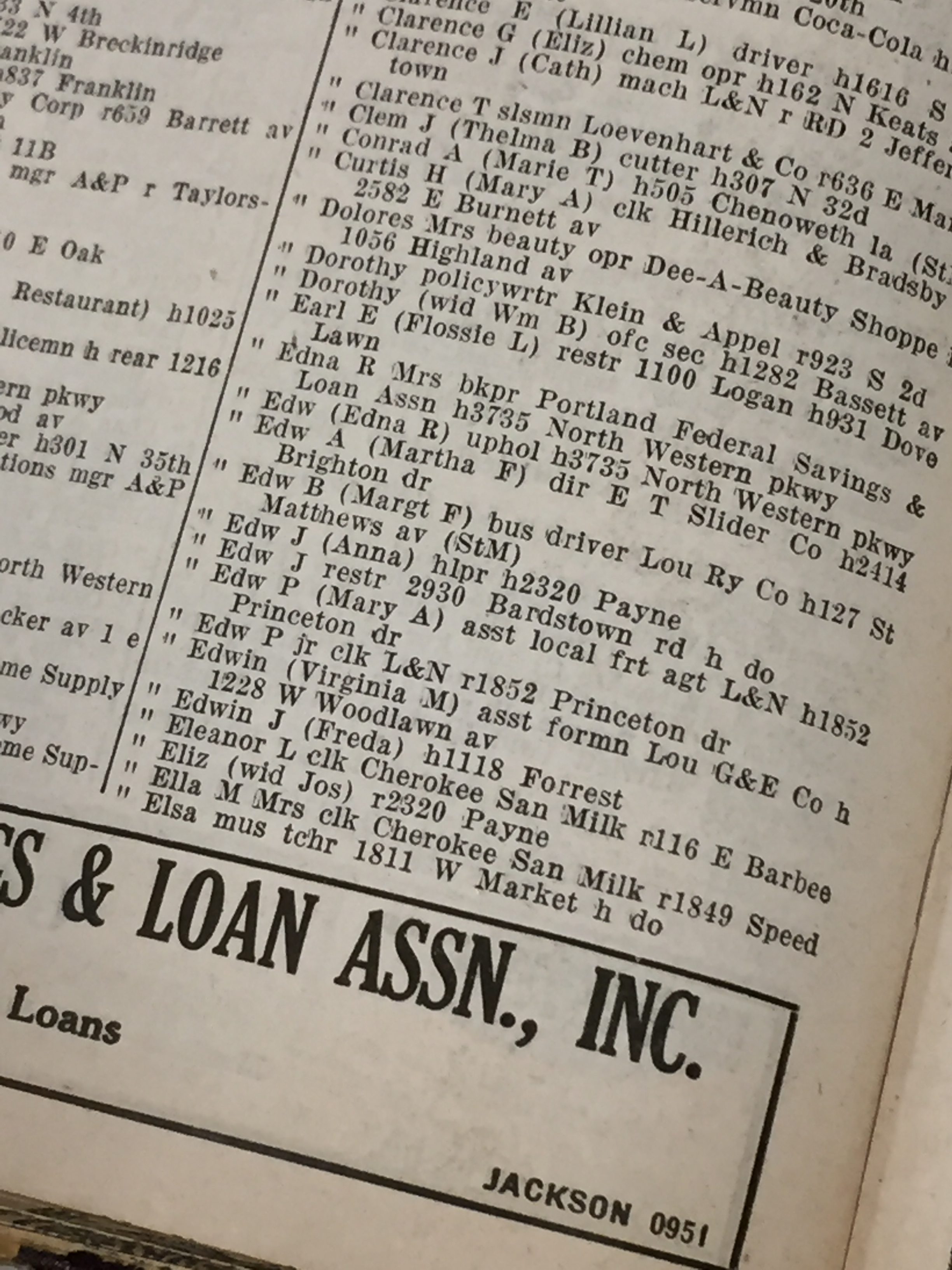

Question: One of our academic researchers was following the life of a single African American woman in the late 19th century. As she turned to City Directories to track residences over the years, she posed a question to us regarding the creation of these directories. She wanted to know who was included in these yearly guides. Obviously, not an entire household, but not always the head of household either. Was everyone included in a City Directory or did you have to pay to be listed? After all, these were valuable resources for advertising your business during that time. As I started digging for more information, I noted that most of our directories, regardless of year were produced by outside companies – not city, state, or federal government entities – nothing official – very much like today’s phone books.

As I started digging for more information, I noted that most of our directories, regardless of year were produced by outside companies – not city, state, or federal government entities – nothing official – very much like today’s phone books. Throughout the many decades of their publication, advertisements can be found each year in the local newspapers, announcing the availability of a new City Directory – obviously offering said directory for sale, or better yet, offering subscriptions to the yearly updates. The popularity of these directories also drove sales for large advertisements within them – a pretty lucrative endeavor for the publishers!

Throughout the many decades of their publication, advertisements can be found each year in the local newspapers, announcing the availability of a new City Directory – obviously offering said directory for sale, or better yet, offering subscriptions to the yearly updates. The popularity of these directories also drove sales for large advertisements within them – a pretty lucrative endeavor for the publishers! Canvassers were hired to begin work in the fall of each year.

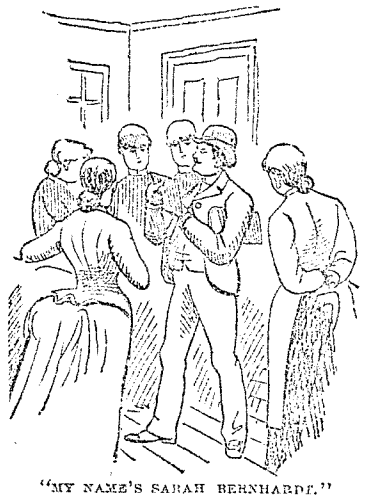

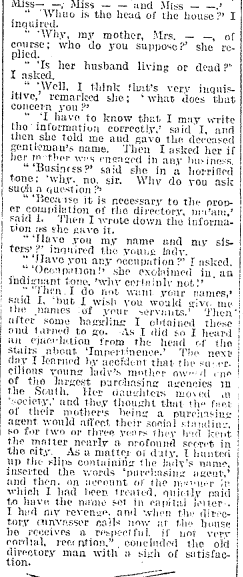

Canvassers were hired to begin work in the fall of each year. Sometimes, our ancestors did not want to be recorded – as it is noted in this article, those who were running from creditors, or the law, or involved in illegal activities might give an alias – just our research luck!

Sometimes, our ancestors did not want to be recorded – as it is noted in this article, those who were running from creditors, or the law, or involved in illegal activities might give an alias – just our research luck! One of my favorite stories from this article came from a household of just women: a single mother/widow – who happened to be a business owner. The household was wealthy enough to employ servants – thereby creating a brief period of confusion. The woman’s young adult daughters were of no occupation, and spent their days at home attended by the servants. The Canvasser arrived and asked about the head of the household and her occupation/business, and then asked about other residents in the home – inquiring about their profession. After first denying their mother’s occupation, the young women thought the City Directory was something of importance at first, and pressed the man to include their names. When they realized that he kept focusing on occupations they became even more offended, declaring that they were NOT of any occupation! The Canvasser then focused on their servants to add to the Directory – which offended the girls even more – apparently, their mother was a large purchaser in the southern region, but the fact had been hidden from their neighbors and social circle as this was considered to be a low class activity. Due to his experience that day, the Canvasser changed his entry for the mother to list “purchasing agent” as a matter of revenge.

One of my favorite stories from this article came from a household of just women: a single mother/widow – who happened to be a business owner. The household was wealthy enough to employ servants – thereby creating a brief period of confusion. The woman’s young adult daughters were of no occupation, and spent their days at home attended by the servants. The Canvasser arrived and asked about the head of the household and her occupation/business, and then asked about other residents in the home – inquiring about their profession. After first denying their mother’s occupation, the young women thought the City Directory was something of importance at first, and pressed the man to include their names. When they realized that he kept focusing on occupations they became even more offended, declaring that they were NOT of any occupation! The Canvasser then focused on their servants to add to the Directory – which offended the girls even more – apparently, their mother was a large purchaser in the southern region, but the fact had been hidden from their neighbors and social circle as this was considered to be a low class activity. Due to his experience that day, the Canvasser changed his entry for the mother to list “purchasing agent” as a matter of revenge.

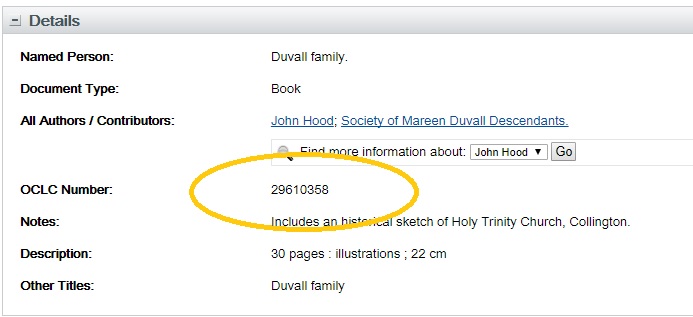

It’s quite a mouthful: Interlibrary Loan. But it would be wise to remember this phrase as it could be your new best friend!

It’s quite a mouthful: Interlibrary Loan. But it would be wise to remember this phrase as it could be your new best friend! Tip #1: Remember these terms: Borrower and Lender. They are exactly as they sound, but the Borrower is not you – you are the patron or customer and the library borrowing on your behalf is the Borrower. The lending library is the Lender. Contrary to perceptions, the ILL transaction is a contract between the two libraries – NOT between the patron and the lending library. This way, both parties agree to certain standards during the transaction, even if things get damaged or lost in the mail, there is already a protocol in place to resolve the situation.

Tip #1: Remember these terms: Borrower and Lender. They are exactly as they sound, but the Borrower is not you – you are the patron or customer and the library borrowing on your behalf is the Borrower. The lending library is the Lender. Contrary to perceptions, the ILL transaction is a contract between the two libraries – NOT between the patron and the lending library. This way, both parties agree to certain standards during the transaction, even if things get damaged or lost in the mail, there is already a protocol in place to resolve the situation.

Let’s Talk Genealogy Materials

Let’s Talk Genealogy Materials Tip #5: If you borrow a book through ILL, READ IT – and do not dawdle! ILL books will usually arrive with a generous loan period of around a month, but many do not allow renewals. So, get cracking on that title once it comes in!

Tip #5: If you borrow a book through ILL, READ IT – and do not dawdle! ILL books will usually arrive with a generous loan period of around a month, but many do not allow renewals. So, get cracking on that title once it comes in!

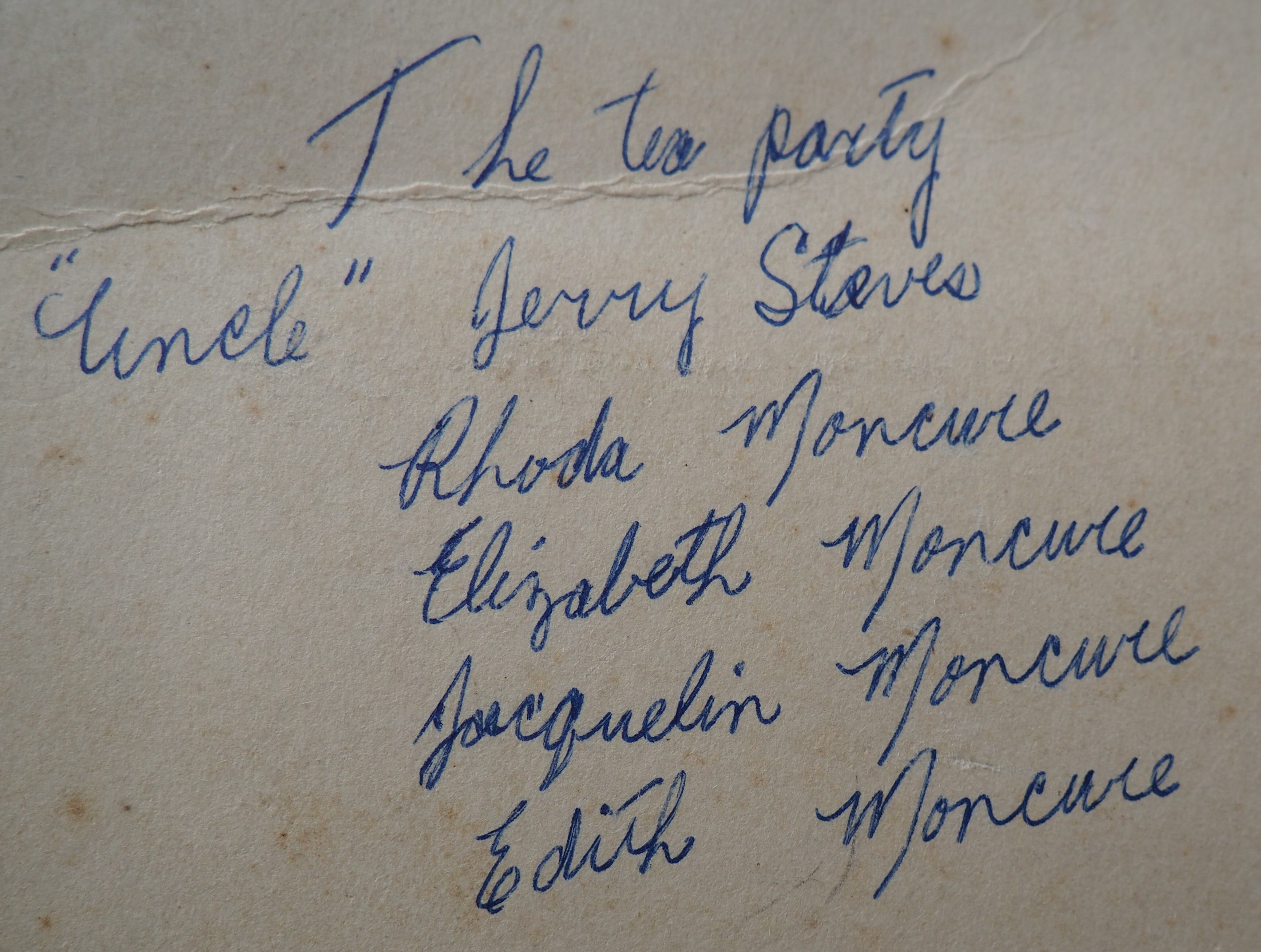

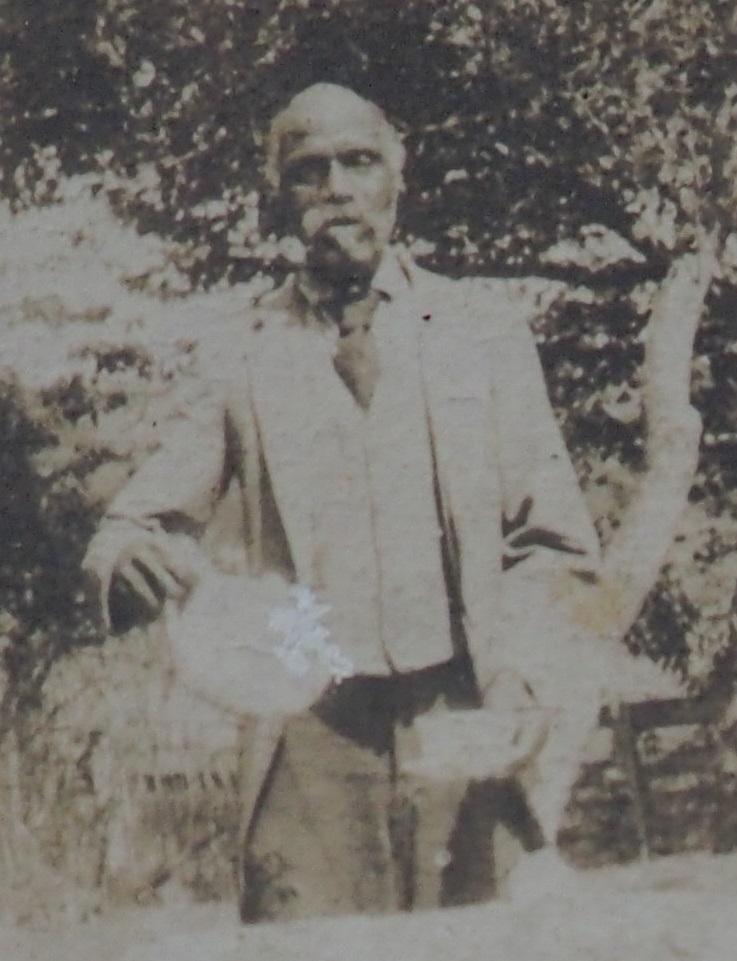

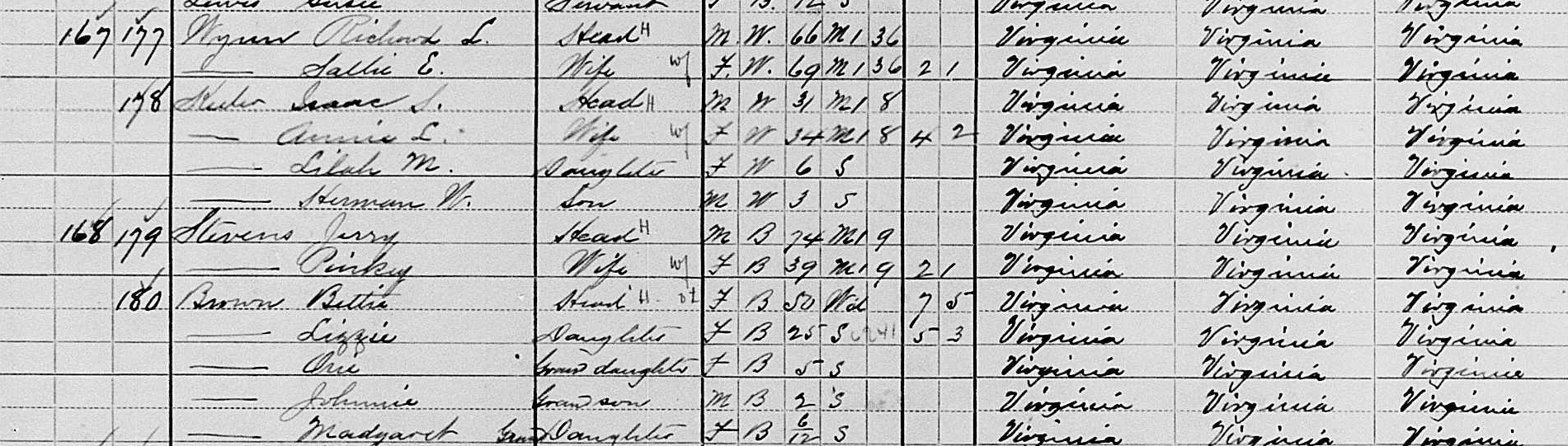

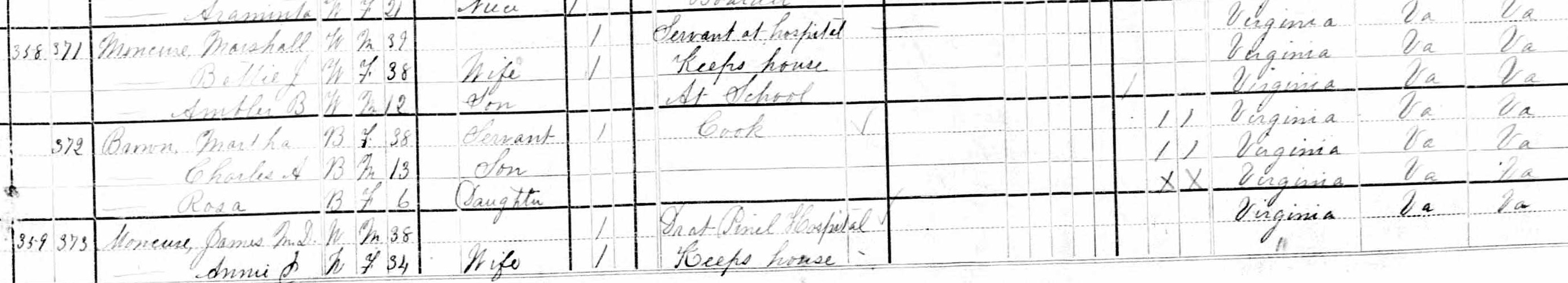

However, a black man named Jerry Stevens was found as a head of household in the same county, but different precinct. He is 74 years old, and living with his 39 year old wife, Pinky! What a hoot! Go, Jerry! Living next door but in the same unit number is a 50 year old widow, Bettie Brown, with her 25 year old single daughter Lizzie Brown, and three young grandchildren with the same last name. Is this Jerry’s daughter and her household? Quite possibly. Of course, they could be Pinky’s sister and family.

However, a black man named Jerry Stevens was found as a head of household in the same county, but different precinct. He is 74 years old, and living with his 39 year old wife, Pinky! What a hoot! Go, Jerry! Living next door but in the same unit number is a 50 year old widow, Bettie Brown, with her 25 year old single daughter Lizzie Brown, and three young grandchildren with the same last name. Is this Jerry’s daughter and her household? Quite possibly. Of course, they could be Pinky’s sister and family.

I am writing this post with gritted teeth and a fake smile upon my lips – retaining a professional demeanor in the face of such a dangerous fallacy can be almost impossible. But I promised you undiluted genealogy – and here comes test case number 1! Quick – go get a cup of tea before reading further!

I am writing this post with gritted teeth and a fake smile upon my lips – retaining a professional demeanor in the face of such a dangerous fallacy can be almost impossible. But I promised you undiluted genealogy – and here comes test case number 1! Quick – go get a cup of tea before reading further! I was recently told a scary story (just in time for Halloween) about the construction of a new county courthouse – the locals in charge of building said courthouse, decided to opt for a closet sized research table to access records, because “No one conducts onsite research anymore – it’s all available on Ancestry!”

I was recently told a scary story (just in time for Halloween) about the construction of a new county courthouse – the locals in charge of building said courthouse, decided to opt for a closet sized research table to access records, because “No one conducts onsite research anymore – it’s all available on Ancestry!”

In short – always think of research as a multi-dimensional process. We are fortunate enough to have wonderful records at the tip of our fingers via super digitization efforts of many – but our research should NEVER stop there! Our storehouses of history contain the family records we need: Bible records, genealogy research files, correspondence, diaries, photos, school and Church records, etc. A fundamental principle of the

In short – always think of research as a multi-dimensional process. We are fortunate enough to have wonderful records at the tip of our fingers via super digitization efforts of many – but our research should NEVER stop there! Our storehouses of history contain the family records we need: Bible records, genealogy research files, correspondence, diaries, photos, school and Church records, etc. A fundamental principle of the